I remember the moment my self-awareness expanded to include eroticized curiosity about other people—I was five when I had my first kiss, with another girl, in front of a porcelain Precious Moments clock depicting two dancing children. “You do what the girl does and I’ll do what the boy does,” she said, as if they were kissing at all. Though we’d not been consciously privy to it, we were miming, best we could, a truth we knew existed in the ether of human intimacy. The moment would become emblematic of my forever-struggle to extricate my own sexuality from my interest—sometimes fearful, sometimes titillating—in “what the boys do.”

I recalled this first kiss—and all its swirling emotions—while watching a scene in Camila Saldarriaga’s Spanish-language film, ¡Mais Duro! Amalia (Sara Montoya), the 14-year-old protagonist and narrator, is watching a film in bed with her friend Laura (Alejandra Chamorro). The day is hot, and the two are sweating. There’s nothing particularly intimate about this moment, save for the sudden shortness of Amalia’s breath and her inching nearer to Laura, newly, visibly aware of her need to feel close. “Have you ever kissed anyone?” Laura asks, abruptly. Amalia is nervous; Laura notices, but seems not to care. “No, have you?” “Of course.” Laura turns away—nothing more. The absence of a kiss can be as awkwardly tender as the kiss itself.

The absence of a kiss can be as awkwardly tender as the kiss itself.

Set in 1990s Colombia, !Mais Duro! (Portuguese for “harder”) is based on a short story by writer and illustrator Amalia Andrade, and is as much about the lead character’s own sexuality as it is about her curiosity in what, she explains, her “guy friends talked about…when they were being boys, without me.” My eventual interest in the secret lives of boys was always conflated with self-referential tension. What did their actions mean for me? Why was I no longer their playmate, but either the object of their pervy gaze or their disgust, their preferences the new determinant of my sexual valence?

In the press materials accompanying the film, Saldarriaga writes about watching porn for the first time, “two months after Mom decided to leave us.” Of this unnamed illicit film she says: “[It] redefined my life and my sexuality as a woman.” She doesn’t quite know why, she adds, but I suspect it’s for the same reason my first kiss (and later, my first glimpse of scrambled porn) left me feeling at once excited, totally confused, and uncomfortably alone. When Amalia learns the boys have figured out how to watch distorted porn on a Brazilian channel—“you could see thongs and kisses and women yelling mais duro”—a new mission to see more porn eclipses her interest in whatever the boys talk about. It’s hard to know if she wants to get deeper insight into their world or her own.

It’s probably the latter—Amalia is painfully introverted. ¡Mais Duro! opens with an inexplicably barren forest before panning to what might be the opposite of fallow woods: a teenage girl’s bedroom, teeming with life on the verge of blooming—pink Donald Ducks, roller skates, nail polish.

She is not so much socially awkward as she is perpetually freaked out.

This is the only place in which Amalia doesn’t look mostly terrified. We know she is shy because unless she’s brushing her hair on her bed, she wears a permanently nervous expression, as if she’s always on the verge of running out of breath. She is not so much socially awkward as she is perpetually freaked out.

Amalia’s inquisitiveness, though, is governed by a peculiar, monolithic calm, a sturdiness buttressed by her need to obtain more information, see more skin. So when Carlos (Guillermo Blanco)—a boy who’s just kind-of her friend—offers to trade her a tape of “almost porn” for a glimpse of her underwear, she acquiesces. He asks while playing a Game Boy, casually, with the sort of nonchalant confidence only people with inherent privilege have. Amalia may not fully know herself yet, but Carlos is already aware of his disproportionate power, simply by virtue of his being a boy. “I thought it was the most absurd request,” Amalia says in voiceover. “So absurd that I said nothing.”

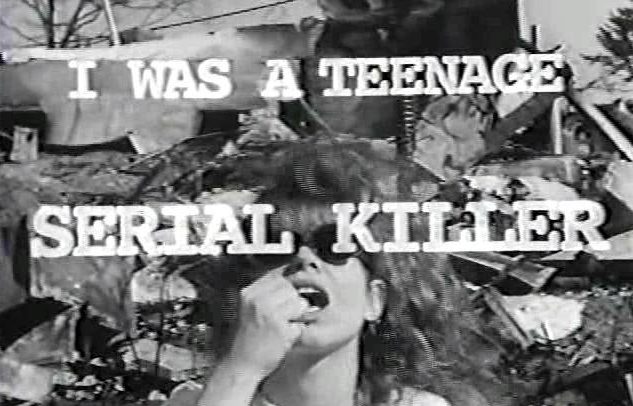

When Amalia flashes him her underwear later that day in the woods, he shrugs, his reaction flat and fruitless as the landscape itself—he just wanted to make sure he could do it, and it’s a silent sort of violence. He gifts her no porn, either. It’s a copy of Kids, Larry Clark’s eponymous coming-of-age film. The exchange is fleeting, and when we return to Amalia’s room, where she’s watching the film in bed with the aforementioned Laura, the change of scenery feels like safety. As the camera pans over their underwear, the gaze is gentle and far removed from Carlos’ in the woods: no power dynamic, no leering disinterest—only soft comfort, two girls familiar with each other, ultimately still children. The banality of Carlos’ nastiness is dissolved, immediately, under the weight of their tenderness. After Laura asks her whether she’s kissed anyone, Amalia’s longing is almost palpable.

“The uncomfortable silence, Laura’s leg over mine as she always did when we watched movies together…I’ll never forget,” Amalia muses. Though understanding boys was always deeply frustrating for me, it was bonds with the cool girls, both sexual and platonic, that seemed the most elusive, my lust to both be like them and be with them. Amalia walks to school the day after watching Kids, and this time, the camera focuses not on her face nor her neurotic distress, but on the scene’s entirety—Amalia traversing down the street, in the world, not necessarily more confident but certainly more cognizant. Confusing desire is its own kind of self-affirmation.

Monica Uszerowicz is a writer and photographer in Miami, FL.