“She really was an unfortunately overlooked director.”

Charlotte Selb, a colleague, wrote this in an email to me nearly a year ago. The filmmaker she was referring to was Michka Saäl, who had passed away suddenly after a quick illness in 2017. “As a woman, an immigrant and just somebody who wasn’t much of a festival politician, she wasn’t always getting the recognition she deserved,” Selb continued, succinctly summarizing the reasons why many talented filmmakers find themselves left out of the Canadian and global canons. Saäl’s passing and the question of recognition coming too late made Selb’s words all the more poignant. We talk a lot here at cléo about changing the film canon, but this work is slow. Sometimes, as in the case of Saäl, it can feel like it comes too late.

Saäl immigrated from Tunisia to France before coming to Quebec in 1979 to study painting, then turning to filmmaking to earn her BA and MA in cinema from the Université de Montreal. This combination of artistic mediums would go on to influence her filmmaking practice, in both form and content, for the rest of her career. Her first short, Loin d’où ? (Far from Where?) (1989), is “a rumination on displacement.”[i] A hybrid of documentary and fiction, the film focuses on a central character whose inner sense of unrest is juxtaposed with verité footage of the streets of Montréal. Shots of ice flowing on the St. Lawrence river are intercut with scenes of the main character waking up in bed, trying to pull herself from the warmth and into the cold day. As I wrote of the film when it screened at Hot Docs earlier this year: “The shock of the snow and a sense of exile are framed around, and intentionally subvert, Quebec’s motto: Je me souviens.”

This play with words in the short’s opening packs a pointed political punch. Taking Quebec’s motto, which recalls the French colonialist projects of the likes of Champlain and Maisonneuve, Saäl asks the viewer to pivot from their position—be that of a French-speaking Quebecer, an Anglo-Canadian or something else entirely—to consider how words’ meanings morph depending on who’s speaking them and who’s receiving them. Je me souviens? I remember…but what? For Saäl’s protagonist, it’s the North African beaches rather than the Plains of Abraham that are the memory.[ii] Though running a brisk 24 minutes, Loin d’ou ? showcases a clear cinematic vision (particularly the director’s pull towards the poetic) and encapsulates many of the topics that Saäl would continue to explore in her later work: race, exile and those who live, often not by their own choice, on the margins.

Loin d’ou ? showcases a clear cinematic vision (particularly the director’s pull towards the poetic) and encapsulates many of the topics that Saäl would continue to explore in her later work: race, exile and those who live, often not by their own choice, on the margins.

Her first feature, L’arbre qui dort rêve à ses racines (The Sleeping Tree Dreams of its Roots) (1992), embodies these themes with both poetry and poignancy. The film follows two friends, one Jewish-Tunisian (played by Saäl herself), the other Lebanese-Christian (Nadine Ltaif), and is interwoven with multiple interviews of Montrealers from different cultural backgrounds. Writing in Le Devoir upon the film’s release, Clement Trudel said: “Saäl allows us to rediscover a Montreal that’s as colourful as a rainbow: Tunisian restaurants—where the owner claims to love the cold!—Sephardic Jews getting married, walking on the street […] illustrates the mix of cultures that Michka Saäl is highlighting, while at the same time she sometimes resorts to exoticism.”[iii]

As Trudel hints, there is a sense that the film is perhaps too naively hopeful in its portrait of “integration,” especially in its political climate. But L’arbre also offers a complex construction of identity through its formal choices. Opening with biblical references to the matriarch Sarah, Saäl then dives into the inner lives of her characters. Cutting between present-day Montreal, Lebanon, the white villas on the coast of Tunisia, apocryphal home videos and shots of newspaper headlines talking about war between and Arabs and Jews, Saäl collapses thousands of years of history and oceans into less than five minutes. The effect, however, isn’t reductive, but rather suggestive of the vastness of inner lives, the oceans we contain in ourselves.

Saäl made a medium-length film (Tragedia, 1993) then returned with the feature doc Le violon sur la toile (The Violin on the Canvas) (1995). Made with the National Film Board (as was her first feature, though Le violon is available on the NFB’s website), Saäl profiles Eleonora Turovsky, a violinist and artist in Montreal. Like Saäl, Turovsky also immigrated to Montreal (in her case from Russia) and is also Jewish. Far less personal than L’arbre, and much more conventional in form, Le violon still retains poetic touches and lets Turovsky’s music, not just her words, create her portrait. In one scene, Saäl films Turovsky’s paintings, which have been hung in a way that makes them appear to be floating in black space, as the musician’s own music plays. Like Saäl’s other films, which were often neither just doc or fiction, here too the director merges her character’s two media of creative output and challenges the idea of categorization and medium specificity; yet again, Saäl resists categories in favour of exploring artistic expression. The result, as Francine Laurendea wrote of the film in Le Devoir, is “creativity as an antidote to exile.”[iv]

Saäl’s next feature was 1998’s La position de l’escargot (The Snail Position). Unfortunately, the film remains difficult to find[v], though its reviews at the time were very favourable, one calling it an “urban fable.”[vi] As with L’arbre, the autobiographical trickles in. In an interview with La Presse, Saäl said: “I started to write this film with the fantastical premise: what would happen if, one day, my father, who I never knew, appeared at my door?”[vii] Indeed, the film is dedicated to her unknown father. What is further striking about this interview is the positioning of the film as “ethnic”; it’s an outlier for the fact that it’s not centred on a white family. La Presse even drew attention to the fact that it had an “ethnic casting that is rarely seen in Quebecois cinema.”[viii] Saäl, for her part, gave the most simple of “explanations” that suggest a de-centering of who gets to define exactly what Quebecois, or more broadly Canadian cinema, looks like: “I’ve lived in Montreal for more than 15 years, and [this film] is what I see around me. I would think that Quebec film should reflect that reality.[ix]

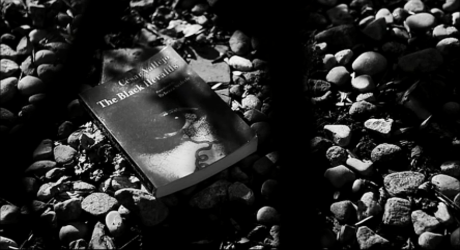

Saäl tackled this topic in her next and most overtly political film, Zero Tolerance (2004). The film embeds the viewer with the police force of Montreal, who all too easily expose their ingrained institutional racism in the policing of people of colour. It also marks the first of three films where Saäl explores policing, and then more specifically incarceration: Les prisonniers de Beckett (Prisoners of Beckett) (2005) and Spoon (2015). (In between she also directed China Me and A Great Day in Paris). A Canada-France co-production, Prisoners follows a prison theatre group in Sweden who are mounting a production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. In a set-up where the tragic irony is all but comically predictable, Saäl refuses convention in favour of diving into the existential, like the iconic play at the heart of the story.

It is Spoon, however, that feels like a formal and political distillation of many of Saäl’s themes. Writing on the film for Hot Docs, I noted: “Spoon builds on her past documentary work and is infused with her signature poetic style. Here, she explores her relationship with an incarcerated [Black] American man, Spoon, through their dialogues, his poetry, dance and the Mojave Desert.”[x] As Saäl develops a friendship with Spoon, the documentary returns to her more personal lens, and once again she uses multiple mediums—Spoon’s spoken words, dance scenes—to grapple with the complexities of living life, both outwardly in our relationships with others but also when it comes to the vastness of the inner lives of individuals.

Saäl’s latest work, New Memories, bowed at RIDM earlier this year, is a documentary about “the camera of Anne J. Gibson.”[xi] Set in Toronto’s Kensington Market, the documentary examines human connections and the complexities of observing life through a camera lens. Through a crowd-funding campaign and with the dedication of Saäl’s partner, Mark Foss, the final film that Saäl was working on (Mavericks) will also be completed soon. Over email, Foss explained he’d “been working on post-production this fall, and we expect to finish in early 2019.” This, as he notes, will also be the 30th anniversary of Loin d’ou?, her first film. Thankfully, this means Saäl’s oeuvre will continue to grow. And, if we continue to discuss and explore Canada’s filmmakers beyond the “familiar,” perhaps our national canon will continue to grow, too. Maybe it’s not too late after all.