Mary Stark is a hands-on artist whose film installations and performances demonstrate that there’s a place for grace in the heavily mechanized world of movie-making. The Manchester-based artist has spent the past half-decade developing a film practice that juxtaposes the delicate and ephemeral (represented in her work by thread, light, music and speech) against the comparatively sturdy properties of celluloid and its accompanying mechanisms. Her work, which ranges from live performances to massive quilts woven from discarded film reels, challenges the film industry’s material and commercial inaccessibility: typically, the bodies, currencies and machines that bring a film to life are kept hidden out of frame, noted in neat ledgers, stationed in laboratory fortresses, and locked away in projection booths.

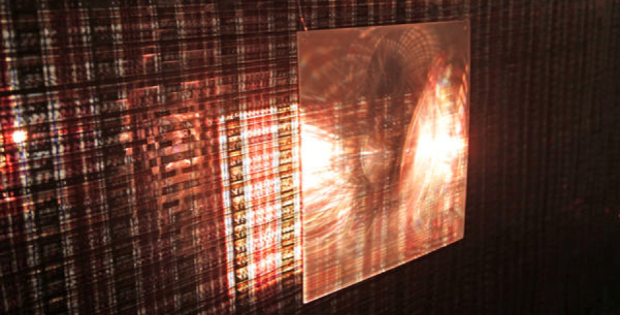

Stark, on the other hand, brings illusion and wonder out of those locked spaces and to the fore, creating works that suggest new methods of exhibiting film as material. Salvaged celluloid dangles loosely in front of projector light, creating ethereal bands that dance on every surface of a performance space. A projector, placed in plain view, spits out film strip into Stark’s expecting fingers, which gently guide the drooping celluloid into a film can on the floor. In her earliest film work, Stark’s woven film tapestries are lit by unspooled projectors and use magnifying lenses to reveal the impressive material abundance of a feature film print.

Despite these decidedly experimental approaches to film exhibition, Stark’s efforts are still rooted in the desire to communicate the history of not one, but two beloved industries: film and textile. She aims to retell stories pertaining to each medium’s industrial processes, specifically to the considerable roles that women have played (and continue to play) within those processes. Her efforts to reshape physical spaces through her performances has led her to elicit a “voice”—what she calls a “noisy feminist presence”—from her materials, pushing herself to pair her tactile manipulations with aural stimuli that ranges from music, to humming projectors, to rattling optical sound, and her own Mancunian-inflected speech.

Whether her body is physically present in an installation or left as a trace in the labour that has gone into its preparation, Stark has developed a genuine body of work whose material heaviness is matched by a palpable corporeal elegance, all of it held together by the loose ends of film and thread.

cléo: You studied art before you started working with celluloid and moving images. What was the catalyst that led you to incorporate film into your art practice?

Mary Stark: My obsession with the materiality of film has come from its invisibility, something hidden in projection booths and laboratories, as well as its increasing demise in recent years as digital technology has become the primary means of viewing moving images. Before 2010, I was completely unaware of how the filmstrip is handled and treated in conventional filmmaking processes. I’d studied embroidery and had a solid grounding in hand and machine stitch before I started making videos. I moved back to Manchester to study photography, and soon after discovered a reel of 8mm film in a junk shop. It seems crazy now, but until that point I had never come into contact with a filmstrip other than negatives from still photographs. I had never fully contemplated the moving image as a photographic object. I held the string of tiny photographs in my hand up to the light and thought: “This is a thread.” From that point I have been exploring the relationships between textile practice and filmmaking.

How has the link between film and thread shaped your relationship to the medium?

My background in photography and embroidery means I am not constrained by filmmaking conventions and in fact I enjoy subverting traditional expectations. At first, all the film I came across was found footage and I never considered shooting my own films. I began buying projectors and asking around cinemas for abandoned reels. My immediate urge was to cut and weave film into fabric. I was interested in how the weave structure might reshape existing narratives.

After I accidentally burned a film in the projector, an archivist weaned me off traditional projection and encouraged me to think of other ways to present my work. I discovered that unspooling a filmstrip in front of the projector’s light would cast shimmering reflections around a dark space. I made a lot of photographic prints enlarging woven film in the darkroom, so I was dealing with the filmstrip simultaneously as a still image, a photographic object and as a light reflecting material rather than a projected moving image.

With a few exceptions, I wove entire films because my main obsession at that time was to see how durations translated into an expanse of space, i.e. what does ninety minutes of 16mm look like if you weave it into a fabric? The largest woven film I made was 4×2 meters, which took about a week to weave. But there are limitations: I currently don’t have a space big enough to weave a feature film on 35mm!

Presenting a woven film in a gallery space allows us to see the material’s durability, weight, and intrinsic, beautiful shimmer. But did you ever worry about losing the content of the found footage you were working with?

I was always interested in the titles of the films, and chose films that somehow referenced cinema: A Gift of Sight, The Wonderful Lie or That’s Entertainment! But my primary interest lay in the material properties of film; the content of the image was always secondary. That’s Entertainment! is interesting, because it’s a history of classic MGM musicals from the 1920s through to the 1970s. When I watched the film, I was just amazed by the elaborate sets, costumes and the showmanship, such as Estelle Williams wearing a sequined cat suit diving from a tower of fireworks through coloured smoke into a swimming pool, all with a smile on her face. Films back then could really revel in the spectacle of cinema, and there’s a tangible visibility to the labour that went into each production. They just don’t make films like that anymore.

Weaving film and presenting it in front of an unspooled film projector denies the audience access to that spectacle, forcing them to focus instead on the spectacle of the material and its presentation through an apparatus. They might imagine the film or remember it if they saw it, but the images themselves are hidden. It also does away with the idea of invisible cuts, since the viewer can see one or two hundred cuts and the splice tape that join and hold the whole thing together.

Editing seems to be of central importance to your process.

Perceiving editing as stitching and film as fabric were obvious and intuitive comparisons for me. This understanding was led by touch, before any concern with images or sound. This is definitely born out of my training in textile practice, which involves sustained handling of materials and develops heightened sensitivity to properties beyond how they look. Fabrics and yarns are considered, for example, by their weight, elasticity, softness, durability, opacity, how they work with light, how they can be worn on the body and function in space.

Rather than negotiating film through the lens of a camera and thinking of it as a visual duration and an image on a screen, my approach is led by directly handling the filmstrip and considering film as a sculptural mass, exploring how it can be presented as a visible tactile material and placed centre stage. Playing with how it reflects light, loops through architectural spaces, can be worn on the body, and stitched on the sewing machine.

You wrote the name of editor and author Walter Murch at the center of a cluster diagram in your notes during a residency in Barcelona in 2013. He’s written about women’s roles as editors in the silent era. Was his inclusion in your notes linked to those writings?

It was. In In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing, Murch uses the metaphor of film as fabric and editing as stitching to emphasize how film editing can be negotiated through relationships to the human body, rather than dictated by a machine or a computer. According to Murch, in the early twentieth century up until 1930, workshops full of women edited with a magnifying glass and a pair of scissors, using the measurement of the tip of their nose to their outstretched hand to work out durations of time. It is so useful that this has been written about, but the story of many anonymous women’s work is still told through the voice of a man at the top of his field in the commercial film industry. Murch’s description of the women editors paints a very nostalgic, romantic picture, as if that way of working is long gone, but there is in fact a vibrant international field of artist filmmakers who continue to edit and create films entirely by hand.

Although tailoring has always been a profession shared by men and women, the history of weaving, sewing, and embroidery really calls to mind the history of women’s labour and leisure. Since your work depends so heavily on these histories, is it safe to consider you a feminist artist?

I understand feminism as striving for equality and diversity, challenging limiting stereotypes and the oppression of marginalized voices. I didn’t start out thinking how I could explore feminist concerns through my art practice, but feminism has become an important and enriching aspect. At the same time, taking on a feminist perspective means I want to avoid singular readings and not feel pinned down by defining characteristics or terminology. So my work does explore feminist concerns, but within a rich contextual framework informed by a variety of ideas and elements. I’m inspired by discussion of the materiality of film; haptic perception; blurring definitions of sound, noise and music; performance as a critique of consumerism and the art object; Manchester’s industrial heritage; technology, culture and obsolescence.

Can you talk a little bit more about your recent attempts to, as you’ve called it elsewhere, “create a noisy feminist presence in experimental film” via manipulations of optical sound? What is being articulated through this process? What has yet to be articulated?

Noisy feminist presence refers to a doctoral research project I’ve been developing for a few years. Exploring feminist concerns has helped me focus on investigating metaphorical “voices” derived from fabric through the technology of optical sound. I am exploring rich and yet often overlooked connections between textile practice and voice through making photograms of fabric, lace and thread, which transform into metaphorical shouts, cries and yells when projected. Creating sounds from fabric, a supposedly silent inert material heavily associated with women, domesticity and craft, is a way to call attention to disregarded voices throughout art histories from the twentieth century onwards.

All this has moved my practice into the realms of experimental film performance as optical sound lends itself to film projection. I never started out thinking I’m going to make performances and in fact I find it terrifying. But I’ve come to prefer the sheer terror of performance to exhibiting film installations or objects because it foregrounds the process of making. I like that there is no product at the end and I’m creating a live experience people enter into.