In the remote locales where the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul are largely set, an awareness of global market forces and borders gently lingers. The Thai filmmaker depicts how people at the margins confront and transgress such symptoms of modernity at local, communal and bodily levels, conditioning permeable ideas of selfhood.

The erotic drama Blissfully Yours (2002) explores how touch and intimacy serve as physical and spiritual balms to social oppression. The film follows three characters living in a northeastern Thai town – Min, an illegal Burmese migrant suffering from a mysterious skin condition; Roong, his Thai girlfriend; and Orn, an older women who Roong has hired to be Min’s caretaker. Touch and the idea of “shedding”, made literal by Min’s peeling skin condition, induce transformations in the characters on a normal day that take a profound turn when they enter the jungle one afternoon. The film, inflected with local folklore and history, was lauded for its slow, sensual cinema style, landing it the Un Certain Regard prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 2002. When it premiered in Thailand, it was the recipient of censoring revisions for its explicit sex scenes and nudity, alongside its casting of a real-life illegal migrant to play the lead character.

Inspired by Weerasethakul’s personal experience of seeing Thai police handcuffing two illegal Burmese migrants at a Bangkok zoo, the film examines how one’s relation to freedom and pleasure is shaped by acts of small indulgence. Before being arrested, how did a leisurely day at the zoo already position the women as resistors of oppression? Blissfully Yours, or Sud Sanaeha (“extreme passion” in Thai), follows this line of inquiry, prying into how those facing social oppression capture simple, defiant pleasures under limited conditions.

Born to parents who are doctors, Apichatpong’s work shows a clear interest in illness.

In exploring the precarity and vulnerability of one’s own most basic well-being, Apichatpong examines the human condition in its fragile states and asks what constructive transformations this can induce.

In films from Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2008),about a dying man’s last days, to Cemetery of Splendour (2015), about a sleeping sickness afflicting Thai soldiers, illness is synonymous with catharsis – a state of being that spurs both physical and spiritual change and leads to healing. In exploring the precarity and vulnerability of one’s own most basic well-being, Apichatpong examines the human condition in its fragile states and asks what constructive transformations this can induce. More than serving as a plot device, illness is deployed as metaphor, inscribing itself onto individual bodies that register the effects of their larger social environment. In Blissfully Yours, it is Min’s shedding that unspools a sense of the social prognosis at play.

The film opens with a scene of the three main characters visiting the doctor’s office to examine Min’s rash. Min is “shedding like a snake”, Orn tells the doctor pleadingly. However, as the scene unfolds, it becomes clear there is more than an itch at stake. The women desperately urge the doctor to produce a medical certificate for Min, without betraying their intention to use it for a work permit. Meanwhile, the doctor seems more concerned about Min’s silence as the women swiftly field the questions she directs at him about his symptoms. He stays silent to conceal his outsider status. Shot with a static camera and air of detachment, the scene forces viewers to sit with the futility of their repeated efforts as the doctor refuses to produce a medical certificate due to Min’s lack of passport. They end up leaving the office with only a generic medicinal prescription which they disregard shortly thereafter, setting up the story’s first implied failure – that of official authority to prescribe any solution to their issues.

The film begins by framing the frustrations of everyday life, the implied symptoms of the characters’ social “sickness”. The story roves from their futile attempts to legalize Min’s status – from the doctor’s office to stubborn administrative bureaus – to Roong’s dull factory job painting Disney figurines. Meanwhile, Orn depends on drugs to deal with an unhappy marriage. She expresses a desire to have a child, but she’s riddled with fear since she’s lost one in a tragedy before. “I’m afraid if we have another child, it will drown again,” she confides to her husband. The camera lingers lengthily on mundane details, hands tying up shoelaces and people idling around waiting rooms. Looped back into the same daily obstacles, the languid pace of the text mimics the forced patience, stasis and duress of the characters enduring their unfulfilled desires, their social and spiritual dead ends.

Then, at the 45-minute mark, the film indicates a clear transitional point where the “shedding” of these daily burdens begins. When Roong cuts work early, taking Min on a trip outside the town’s limits, an upbeat pop song marks a decisive narrative departure. A Thai cover of Summer Samba, decked with glittering synths, breaks up the fragmented talk and sense of stasis governing the previous scenes. And then, at the film’s halfway point, the opening credits begin to roll, lending the text a heightened momentum, a sense of plunging deeper into the fiction unfolding. The filming of the road heading out of town guides viewers into the shift in gears, so to speak: before the song prompts the plot’s detour, the camera traces the curves of the roads at length, snaking along suggestively. In a rare moment favouring movement over stillness in the film, it is understood that the story is veering in a fresh direction, a fact further foreshadowed by a close-up shot of Roong’s hand gripping the shift stick, laden with erotic connotations.

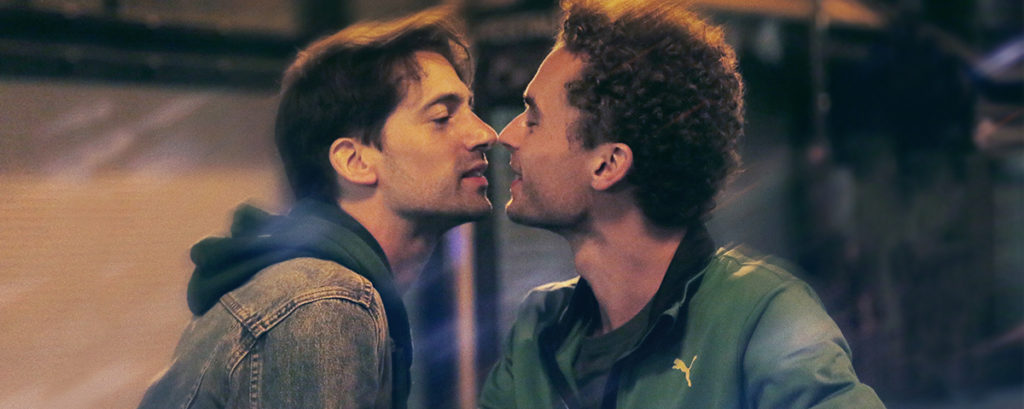

The idea of “getting under another’s skin” begins to be explored with an erotic fervor, reinforced with the camera’s close-ups of flesh and longing looks. The previous confines faced by Min and Roong are “shed” as they enter the jungle, casting aside their social ills from daily life. Min and Roong kiss, fondle, and feed each other – plucking fruit from trees and picnicking, partaking in small indulgences and acts of sustenance. Later, Orn separately makes her way to the jungle, where she finds a quiet place to engage in adulterous intercourse. On a bamboo mat unrolled on the forest floor, she makes love with her husband’s co-worker, her face conveying palpable pleasure and relief.

These small gestures, moments of minute but tender tactility, convey how the characters’ previous stresses are dissolved through simple touch.

Between the obvious sexual acts, shots of hands and touch litter the second half with a less erotic yet equally profound meaning – Orn shown toying with her lover’s belly button; Roong creating a sticky rice cluster to hand-feed to Min. These small gestures, moments of minute but tender tactility, convey how the characters’ previous stresses are dissolved through simple touch. In the dialogue-sparse script, touch becomes the way in which desire, care, and bliss are expressed.

Likewise, the jungle setting helps convey and complement the shift in the characters’ inward states. Like a second skin, the camera sheds its pale, clinical, angular view, flooding each frame with a soft, blissful sunlight. Meanwhile, the jungle provides a steady, comforting hum of a soundtrack that seems to compensate for the characters’ quietude as they engage in acts of intimacy. When Min and Roong first kiss on screen, for example, the sound of bees becomes amplified. The jungle lends the text an earthy eroticism, mimicking the characters’ wild and unrestrained sense of bliss.

Another aesthetic choice with tactile implications is the superimposed drawings that flash intermittently across the screen. These drawings, etched out with a shaky, infantile-looking hand, are the implied work of Min and fill various narratives gaps. One drawing implies that Min’s rash most likely came from hiding in a septic tank to avoid legal authorities. Another shows that he desires not only Roong, but has erotic thoughts about Orn, in a picture he draws of her with large, exaggerated breasts. The drawings substitute Min’s relative silence – the implied outcome of a life sentenced to the margins, while conveying a desire to get close, and to inscribe one’s self on another’s skin. Here, this is enacted on the film’s celluloid. In this celluloid life, Min “explains” his existence has been spelled out and scripted in a language that is not his own. However, by transplanting touch onto the filmic skin, the narrative transformations and possibilities being etched onto the filmic skin itself is made clear.

Min’s liminality and vulnerability, as doubly implied by his status as both a migrant and patient, make him the key figure in the characters’ blissful, subjective shifts in the jungle. Specifically, his illness is what helps both Roong and Orn “shed” their previous unhappiness by inviting them to experience desire, implied by the women’s palpable attraction to him. This includes the repeated application of Orn’s homemade medicine, a strange mix of lotion and chopped-up vegetables, which the women slather onto him in defiance of the doctor’s orders. His skin condition serves as an excuse for them to get close to him, and to share in his personal plight in a way that collectively heals. This idea of renewal culminates in the baptismal imagery of the three’s reunion in the jungle when the women cleanse Min as he lays down in a pond, lapping water over his floating body.

While the sense of bliss permeates each sunny close-up shot, Apichatpong shows that such states of being are only ever temporary and difficult to maintain. He shows this in various ways – for example, the ants that keep overrunning Min and Roong’s idyllic picnic serve as reminders that their makeshift feast will be inevitably gobbled up by the forces of nature. Similarly, while the sun in part serves as Min’s source of healing, he is also constantly told to stay out of it to avoid added itching. Despite Orn’s weariness of water, the element that killed her child, she freely indulges in the water as she cleanses Min. All this points to the ways in which the forces of nature can be both friendly and fatal, but ultimately underlines the danger of exposing’s one’s self to desire.

The finality of the characters’ blissful episode is bluntly underlined by the post-script. A text discloses that Min gets a job in Bangkok; Roong gets a new boyfriend and job working at a noodle stall. Orn is said to continue to work as a Thai movie extra. Pulled out of the narrative world, the viewer is plopped in the matter-of-fact aftermath to cruelly underline the film’s ephemerality.

Apichatpong shows how Min, Orn, and Roong’s search for desire resists the social alienation they endure. In riding out the dull, repetitive rhythm of everyday life with grace, whether it’s using makeshift medicines or committing petty acts of corruption to get by, he confers to them a sense of nobility – a perceptible insistence on pushing the plot forward.

In Blissfully Yours, touch and sensuality aid and dignify the characters’ search for better lives. Bound to jobs and burdens they did not choose, they must find ways to seize pleasure in a system that does not hand it to them.

Bound to jobs and burdens they did not choose, they must find ways to seize pleasure in a system that does not hand it to them.

In defiance, they turn to their own devices and desires, their own homemade medicines and erotic instincts. It is ultimately desire that leads the characters to transform each other’s skin conditions on a level that is skin deep. They soften through desirous touch, becoming one with one another and their environment. Through this, they are able to glimpse bliss. Apichatpong shows how desire, scripted onto skin, and the tender acts of resistance it invites, can serve as alternate prescriptions for social ills.