Documentary film can take audiences behind the curtain to explore institutional spaces that are seldom seen. When that glimpse exposes systemic injustice, audiences may be compelled to empathize and even rally behind a cause. As a means of galvanizing supporters around a struggle, documentary film can be a powerful tool for activists; especially for marginalized activists who may have limited resources to get their voices heard. When applied to a maligned and stigmatized line of work—in this case, sex work—is it possible for documentary, by exposing the realities of those who work in sex commerce, to help sex work activists to normalize their work and protect their labour rights? In terms of shoring up support for their cause by revealing the complex motivations behind sex work, can documentary film change the perceptions of anti-sex work feminists who view it as an industry that demeans, victimizes, and promotes abuse against women?

Two very different approaches to documentary filmmaking on sex work, specifically, exotic dancing, are explored in this piece in relation to questions of agency, feminist alliances, and the writhing female body. The first, Live Nude Girls Unite! (2000, Funari & Query), supports normalizing and regularizing sex work by drawing parallels between the sex workers’ struggle and the broader labour movement. Unlike the first, the second documentary is not based on first-hand lived experience of the sex trade. Frederick Wiseman’s Crazy Horse (2012), with its fly-on-the-wall, voyeuristic style (characteristic of Wiseman’s work), never delves into the experiences or feelings of its subjects, the dancers at the Crazy Horse erotic cabaret in Paris. Wiseman does not explore the labour struggles that were taking place between the dancers and club management at the time. Instead, he focuses on the dancers’ bodies as works of art rather than as political or social agents of change. However, by exploring the artistry of the performance, Crazy Horse has the potential to be used as a political tool by sex workers to alter perceptions of sex work as a dirty, debasing trade.

In Live Nude Girls Unite!, exotic dancer and director, Julia Query, chronicles what life is like for her and her peep show colleagues at San Francisco’s Lusty Lady at a politically charged moment in the club’s history. The film presents nude dancing as a job much like any other. In one scene, the women are working together in the peep show, swinging around poles and gyrating in front of clients behind glass. Watching them do their job feels no different from watching workers in a more sedate setting. They laugh at one another and call jovially across the room, cracking jokes. The women look perfectly comfortable in their workplace; it does not appear to be an atmosphere of coercion. They state the same reasons for working in this industry as would “mainstream” workers: making a good wage, providing for their families, and paying rent.

The women are portrayed not just as bodies snaking around poles but as complex human beings with concerns and interests that go beyond their work at the Lusty Lady. They are made relatable through their personal struggles. Query is a comedian who struggles to earn a living and seeks out sex work as a means to pay her bills. She has never told her mother, a fellow activist, about her line of work. In the confessional scene where Query finally does tell her mother, she makes a very honest appeal for acceptance and understanding. Unfortunately, her mother’s response is not what Query had hoped for: it’s a familiar situation of inter-generational misunderstanding.

The Lusty Lady’s employees are not just facing personal challenges with their work. Frustrations come to a head over a number of issues. The central conflict is with management’s decision to install one-way mirrored glass in the booths, which would allow patrons to film the show without the dancers’ knowledge or consent. Other precipitating factors include discriminatory hiring practices that result in fewer women of colour being hired, and, those that are, rarely being scheduled into the more lucrative private booths. Query follows the ensuing strike and the employees’ successful efforts to become the first and only peep show in the United States with a closed-shop union.

The battle around the bargaining table with resistant managers, the demands of the dancers for paid vacation days, non-discriminatory hiring, and a safe, consensual workplace—these are familiar stories in today’s neoliberal labour landscape. Workers across the spectrum are finding themselves in similar straits in the name of protecting profit over people. Despite this particular struggle happening in an unconventional workplace, the Lusty Ladies’ story of unionization and, after the film’s release, becoming a worker-owned co-op, can serve as a positive model in the broader labour movement.

Considering how familiar these women’s labour issues are, coalition-building seems like a logical next step. However, the challenges sex workers face in being accepted as allies in other social justice/feminist circles are very apparent. Query’s mother, Dr. Joyce Wallace, a crusader for “victimized prostitutes,” does not comprehend how her daughter could choose sex work as a profession. In Query’s case, her choice to do sex work is just that: a choice among many others. Query decides to take up sex work to supplement her income but she also enjoys the job and the activism associated with it. Her position of white middle class privilege has afforded her the luxury of making this decision independently, and not out of economic desperation or coercion. Query’s situation has also permitted her to be more selective in the club she works for, choosing one that is more progressive than other institutions.

Query’s decisions indicate that she is not a victim; she is an empowered employee making choices about how she uses her body and sex. Unfortunately, Wallace cannot see past her narrow understanding of sex work to see the overlap in her and her daughter’s activism. Wallace’s dismissal of her daughter’s political work is indicative of the attitudes of many second wave feminists towards sex work, which assumes that all sex workers are exploited and abused. The opportunity for a great partnership and alliance between the two generations never materializes. And yet, the film does an effective job of showing what a potentially productive partnership it could have been.

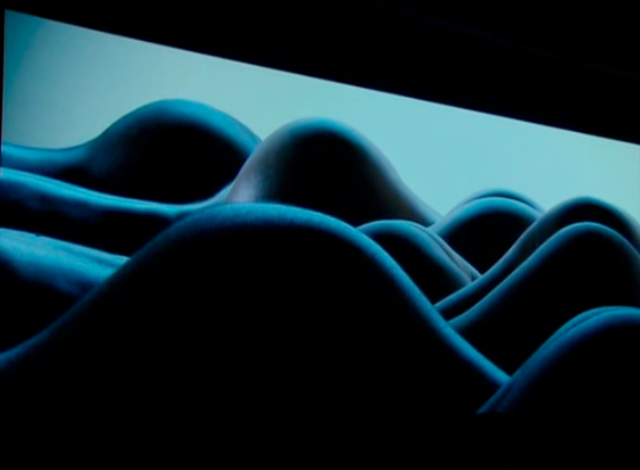

Where Live Nude Girls Unite! advances efforts to normalize and regularize sex work, Wiseman’s film observes his sex worker subjects without ever actively delving into the politics or perceptions of their profession. Wiseman’s primary subjects are the exotic dancers at Paris’ Crazy Horse cabaret, and yet, not once does he interview or offer personal portrayals of these women. Instead, the film uniformly treats its female subjects as a kaleidoscope of body parts. Breasts, bums, and lips twirl by in rapid succession animated by coy musical numbers. The non-dancing scenes that are selected never show the women as being part of the creative process. Those involved in the creation of the show, the choreographer and assistant director, are both men. The assistant director, in one of the few interviews in the film, claims to be “giving women the key to eroticism” through their performance. This is empowering language, and yet, the dancers are never asked for their input or feedback. It’s all very sexy, sure, but that is easy when the audience has been told repeatedly that this is what desire looks like.

This detached observational approach is characteristic of Wiseman’s previous work and his particular mode of documentary filmmaking. Wiseman is known for ethnographically exploring the insides of institutions, recording first-hand events as they happen rather than involving himself in their recreation or interpretation. In Titicut Follies (1967), he reveals the dire conditions of an American mental institution and raises ethical questions by offering an immersive experience rather than actively guiding his audience to predetermined conclusions.

By choosing to include certain images, the juxtaposition of a man’s shadow puppets with the dancers’ first number, for instance, Crazy Horse does raise ethical questions around voyeurism, power and consent. Wiseman’s approach, however, is so indirect that the film risks playing into the arguments of anti-sex work proponents. The Crazy Horse dancers’ bodies are objectified and sexualized almost to absurdity. Posteriors no longer resemble rears as the close-ups get tighter and the body part’s context is lost. The dancers are also never seen making choices for themselves. In their audition, they are lined up side-by-side and sized up by casting directors like show dogs at a fair. Those without the right attributes are unceremoniously dismissed. Staying true to his mode of filmmaking, Wiseman keeps his camera away from the more substantive conflicts between the dancers and club management that were happening around the time of his filmmaking. The New York Post reports that in May 2012 the dancers of Crazy Horse went on strike demanding improvements to their “deplorable” pay. Management refused.

With such a disempowering portrayal of exotic dancing, is there anything that can be used in this film by sex workers to advance their political cause? Despite never seeing the women in the choreographer’s role, they are unmistakably artists. The women study their craft backstage and suggest to one another how to tweak a routine. They doggedly pursue perfection in rehearsals. The film reinforces the artistry and skill involved in this performance. It prompts viewers to reconsider the lack of respect typically conferred on those who work as exotic dancers and can help to shift perceptions that are based on a narrow view of the industry.

Despite presenting very different angles of exotic dancing, both Live Nude Girls Unite! and Crazy Horse provide intimate looks into the inner workings of a trade that is so often misrepresented. These documentaries reveal that the trade is worthy of admiration for being artistically and physically demanding, and is also a microcosm of the broader labour and feminist movements. The same workplace struggles, challenges with coalition-building, and efforts to achieve cooperative control exist within and outside of the sex trade. The creative solutions that sex workers in San Francisco have developed can serve as a rallying call to other social justice activists. At least, we should all be taking note for when it may be our turn on the picket line.