The cabin is well worn, but one gets the feeling this is due to the age of its materials, rather than the use it has had over the years. A record player cracks and pops, and the lilting wail of Jimmy Page fills the air as a flannel-clad man dribbles and shoots a basketball at a rusted hoop. Though these elements all suggest it might be 1977, it is in fact 2077. This aesthetic anachronism is indicative of the importance Oblivion (2013) places on history as a universal narrative and as a roadmap to personal identity. In Joseph Kosinski’s film, history is itself a home.

The flannel-wearing hoops-shooter is Jack Harper (Tom Cruise), a hi-tech drone repairman who lives in a futuristic compound (that more closely resembles a sterile medical lab than a cozy cottage) with his partner, in work and in life, Victoria (Andrea Riseborough). The two work as a “mop-up crew,” monitoring the Earth for enemy activity in the aftermath of a war with alien invaders (known as Scavengers or “Scavs”) that has left the planet battle-scarred and radioactive. Earth has become a terra incognita due to the Scavs’ destruction of the moon—ever a symbol of cyclical femininity, and one that nods to women’s central role in the narrative—which now hangs in the sky as a crumpled, shattered remnant of what once was. Without its gravitational pull, we are told, the Earth fell into disarray; tidal waves destroyed land, which in turn shook and split from earthquakes and eruptions.

Despite the destruction of the Earth’s surface, Jack and Victoria’s home—in a tower high above—displays not a speck of dust or clutter, only gleaming chrome and glass. Even Victoria herself seems a piece of this décor, impeccably dressed in sculptural shift dresses, accompanied by slicked-back hair and pointed heels. Her choice of footwear prompted New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis to opine, “the heels seem a strange choice given, you know, the whole doomsday thing, not the mention the glossiness of the couple’s floors.” But in fact, the heels function in perfect harmony with the film, signifying Victoria as an integral element of this environment—serving the same semiotic function as her hyper-futuristic touchscreen computer, or the meals that appear as anonymous squares of surely nutrient-dense edibles served from individual vacuum-sealed pouches. These objects—of which she is one—loudly and obviously declare this as the future: a different, cold, and calculated environment in stark contrast with the relaxed authenticity of Jack’s cabin. The latter is a hideaway whose existence Jack keeps secret from Victoria. She is too much a part of one world to venture into the other one he has (re)-created.

Jack’s motivation to build such a secretive personal space is rooted in nostalgia, and a particular nostalgic homesickness. Despite being born after the war, he is haunted by images— unsure of whether they are memories or dreams—of a pre-war New York City, where he visits the Empire State Building with a mysterious, magnetic woman he cannot place. Jack feels drawn to remain on Earth, while Victoria is hotly anticipating the conclusion of their contracted time there and subsequent reunion with the remaining humans at an outpost on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. In the stark division between Earth and space, Victoria languishes somewhere in the middle: she is of earth—a human—but longs to leave it behind for the cold clutches of space. Jack, on the other hand, feels inexorably drawn to the abandoned planet. As he achingly laments, “I can’t help but feel that Earth is still my home.” In this sense, history remains an authenticating feature. Jack collects dated objects, and displays them as talismans in his cabin; each is imbued with a sense of authenticity that fills him with longing. Jack considers the past as a homologous entity, an absolute truth in which he finds comfort—even if it is not his history.

With Victoria representing a cumbersome futuristic indecision between Earth and space, it is no surprise that these two elements, and the thematic focus of Oblivion on nostalgia and homesickness, are enacted through its depiction of women. We are soon introduced to Julia Rusakova (Olga Kurylenko), a mysterious Russian astronaut who crash-lands on Earth after spending 60 years in suspended animation. Julia is none other than the mysterious woman who haunts Jacks memory-dreams, and upon her arrival on the planet she also seems to recognize him. It is slowly revealed that everything Jack believed of his own life is false. Julia is in fact Jack’s wife from before the war. Both were astronauts on an international mission to explore a mysterious object that appeared in space. This object (referred to as “the Tet”) is what Jack and Victoria believed to be their decidedly human mission control. The revelation that what he believed to be true is entirely a lie (clumsily set up by the script with a passing reference to a “mandatory memory wipe” in Jack’s introductory monologue) gives way to further dramatic revelations: the alien “Scavs” are in fact human resistance fighters seeking a way to destroy the Tet, and neither Jack nor Victoria are who they believed they were.

Julia’s arrival opens the floodgates of Jack’s memory, and his grainy black-and-white dreams become full-fledged memories rendered in vivid, warm colour. For Jack, Julia represents the fulfillment of the homesick longing he has felt. This is particularly true in the aftermath of the revelation that he is not Jack Harper but rather a clone thereof, one of innumerable exact replicas. In this situation, Julia is the only thing tying him to what he believes to be home. She is, in this sense, his home.

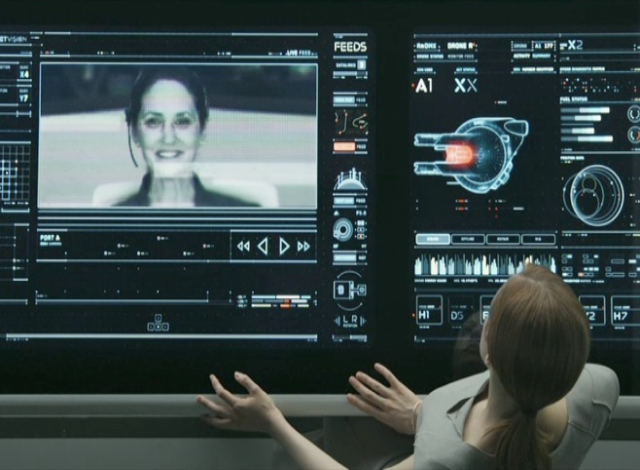

If Julia is one side of a post-apocalyptic Earth-space dichotomy, the Tet, in the anthropomorphic role it adopts for itself, occupies the other side. Though it is revealed to be a sentient being free from any biological elements, the Tet has assumed the image and voice of a woman familiar to Jack, Julia, and Victoria from their days as NASA astronauts. “Sally” adopts the Southern drawl and recognizable speech of this figure in an effort to maintain the ruse it has developed for its clone teams. And teams they are, as Sally has made them. The Tet consistently emphasizes collaboration between Jack and Victoria, asking regularly and almost threateningly “are you an effective team?” Victoria’s consistent answer—“damn right we are,” or some variation—seems to calm Sally. Sally has created them, grown them within the confines of the sleek, mechanical Tet, and released them into the world. While the Tet is asexual and non-biological, it has, in its own way, given birth to them. Motherhood courses through Oblivion’s narrative. As much as the film is mired in nostalgic gazing at the past, it is obsessed with futurity and procreation.

Jack is created by Sally, and actualized by the memories that Julia shares with him. During the final night he and Julia spend together in his cabin, listening to the century-old record player emanate the even older sounds of Procol Harum’s “Whiter Shade of Pale” (in case you forgot how important the past is), Jack laments his insecurity with his identity:

Jack: I’m not him. I know I’m not. But I’ve loved you for as long as I remember.

Julia: These memories are yours, Jack. They’re ours.

It is key to consider this exchange in comparison with Jack and Victoria’s partnership. Though their relationship was romantic, the emphasis was constantly on teamwork. When Victoria finally responds to Sally’s queries with “we are not an effective team,” Sally attempts to kill them both—and succeeds in Victoria’s case. The film disparages the sense of a partnership as a team, treating it as the pathological desire of a murderous evil rather than as a marker of a successful relationship. Jack and Julia, on the other hand, are not treated as a team. Rather than building a future, they rely on a shared past and a universal memory as the mortar to their relationship. Where Sally mothers Jack by creating his physical being, Julia mothers Jack by creating his memories.

Pop psychology would suggest that Jack needs to kill his mother in order to create his own identity. In one sense this is true for Jack, whose identity is in such crisis as to almost be non-existent; and he does indeed kill his maternal creator. In the film’s climax, Jack and the leader of the human resistance succeed in penetrating the centre of the Tet and find themselves face-to-“face” with the undulating mechanical being of Sally. When she realizes their plan to destroy her, she lashes out:

Sally: I created you, Jack. I am your god.

Jack: Fuck you, Sally.

Jack must kill one mother in order to venerate the other. He must destroy the Tet in order to regain a hold on his home, yet in doing so he also kills himself. As important as identity is for Jack, individuality is another thing entirely. Jack is killed, but Jack is only one of many. Another Jack is ready to take his place, and to fulfill his search for home and identity.

The film’s final scene depicts Earth, three years after the destruction of the Tet. Julia is revealed to be living in Jack’s cabin with their toddler daughter, fulfilling the maternality with which she was earlier depicted. She has become the literal Earth mother—tending to her subsistence garden, surrounded by the nostalgic ephemera that Jack collected. She is as much an object in his collection as the record player; she is the analog woman. When the ragtag group of human survivors stumble upon her cabin, the group parts to reveal another Jack, a different Jack. His voiceover declares that he undertook his search for this cabin because of his shared memories with the original Jack. He knew that he would have built this cabin.

“I know him. I am him. I am Jack Harper, and I am home.”

In this world, each clone shares the same memories, and by extension the same entitlement to Julia as an idealized tether for their false nostalgia. Jack establishes his identity and his home through Julia. He has destroyed one mother in order to maintain another. In this sense, home, as a concept and as the physical space of Earth, is indicative of the universalizing nature of the narrative. The film posits a shared history as unifying, when it is instead reductive. To consider Julia’s memories as the building blocks of the identities of innumerable Jacks is to remove her selfhood entirely. She is not a human, but rather a link to a memory of a past, and a home that never was.