“When you’re passionate, are you more free or less free?”

A high school teacher poses this question to his class, and studious protagonist Charlie (Joséphine Japy) cites Nietzsche to answer: “It’s easier to renounce passion than control it. Meaning, we become so preoccupied by it that we lose a kind of freedom.” The excerpted lesson concludes that passion is harmful when it becomes excessive, and like a dutiful student, much of Melanie Laurent’s Respire (Breathe, 2014) attempts to plot the point(s) where passion, invigorating but harmless, tips into excess.

But if the classroom scene seems to raise an either/or problem, Laurent’s film goes on to complicate the presumed exclusivity of its alternatives. According to the actual tumult of Charlie’s relationship with seductive new student Sarah (Lou de Laâge)—which, in the above scene, has not yet begun—passion’s impact is less a question of ‘more free’ or ‘less free,’ or of wholesome liberation versus bad bondage, than an insistence on a messy, dialectical both. Like Charlie, Breathe is simultaneously infatuated with and fearful of the friendship whose dissolution it depicts.

In the tradition of sadistic schoolgirl cinema, Laurent’s film imagines female friendship as uniquely and concurrently erotic and cruel. Thus, not only does “breathe” resonate with Charlie’s asthma and the film’s divisive conclusion, in which Charlie asphyxiates bosom buddy-slash-torturer Sarah with a pillow, it also references the breathlessness of hysterical laughter and the breakneck pace at which girls stumble in and out of love.

In the span of several months, Sarah joins Charlie’s class, ingratiates herself with her circle, awakens her to a thrilling new mode of female friendship and refocuses that intensity toward Charlie’s destruction. While Charlie already has a close friend in wan classmate Victoire (Roxane Duran), Sarah is a different animal—not just beautiful but carelessly so, from the moment she mounts the balance beam in the school gymnasium, striking a practiced arabesque before indifferently returning to her seat.

Sarah claims to have moved from Nigeria, where her mother remains working with an NGO. In a key sequence that initially seems to part from Charlie’s perspective, we watch Sarah ride the city bus to a housing project where the camera tracks along the building’s outer wall, peering Rear Window-style through the windows of Sarah’s unit as the lights figuratively and literally come on. The loathsome aunt with whom Sarah is supposedly staying is actually her mother, surrounded by bottles in the dark. As she hammers on Sarah’s bedroom door, the frame shifts to show Charlie listening just outside; we never really left her, but merely followed her following.

Because of its virtuosic camera movement, it’s tempting to see this sequence as unique to Breathe’s overall style. But, while it’s unusual for the camera to directly express Charlie’s point of view, the practice of revealing Charlie in peripheral relation to other figures is consistent throughout the film. The film introduces her by way of her sneakers on the bedroom floor and the rising alarm of parental bickering off-screen. We follow Charlie’s back down the stairs; in the kitchen we see her parents’ faces while hers is initially shrouded by hair. Charlie’s quasi-estranged father offers her breakfast and chides her mother for sniffling at the sink. His admonishment—“Wipe your nose”—and the wordless reaction shot that follows prime us for the film’s abiding fixation on domestic discord and, more specifically, on women failing to get their bodies under control.

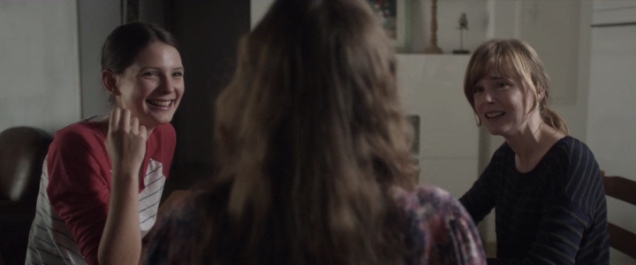

Later, in a scene that presages the revelation of Sarah’s home life, Charlie and her mother flank Sarah at their kitchen table, the camera fixed behind Sarah’s head. We cut in on Sarah’s story already in progress, such that her performance and her listeners’ captivation outweigh the anecdote itself. Bemoaning her aunt—“She has a weird laugh. A cackle!”—she impersonates the fictitious woman, producing a high-pitched trill of laughter to Charlie and her mother’s horrified amusement. “It’s unbearable,” says Sarah. She cackles again.

In his book on gross-out cinema, William Paul observes that “laughter…is also a recognition of the pleasure in screaming itself. In both cases, the response is equally vocal, as the response to a horror film can be as raucous and audible as the response to a comedy.”[i] Like screaming, such laughter may be eruptive, potentially cathartic, and fundamentally violent. It’s in this register that laughter, specifically women’s laughter, echoes throughout Breathe, announcing its capacity to accompany and invoke experiences that have little to do with amusement. Sarah’s impression of her “aunt’s” maniacal laughter is uncanny in that it deforms familiar sound, and more so because the film visually withholds its source. In the absence of a mouth the laugh sounds thrown—as if, once emitted, the sound of Sarah’s cackle exceeds the fact of her, laughing.

The banal response to laughter is to ask, “What’s (so) funny?” and expect a conclusive answer. Sarah’s unsettling cackle, like much of the female laughter in Breathe, is to some degree simply hysterical. If hysteria connotes excess (as in, emotions and behaviors in excess of conventional expression), then hysteria may be evident not only in film content, but in a film’s capacity to deploy form hysterically, in excess of narrative meaning.

There is a second, more pronounced instance of hysterical laughing in the above kitchen scene, after Charlie’s father phones and her mother takes the call upstairs. Sarah and Charlie listen, sharing the receiver, until Sarah interrupts the conversation on Charlie’s mother’s behalf: “Leave her alone. Fuck off.” Aghast, Charlie’s mother runs downstairs; Charlie herself seems stunned. But as Sarah shruggingly plays off the outburst, Charlie is increasingly overcome, until both girls succumb to the irrational laughter of people on the verge of inexplicable tears, unable to catch their breath.

This laughter metastasizes into an entire montage, the narrative economy of which neatly evokes the sudden momentum of teenage alliance. Charlie and Sarah are fast friends—giggling in class, in a bed, over the phone… amid less and less context until laughter is the sole focus, the very figure of inseparability. Dancing surrounded by friends at a party—laughing without talking—they’re effectively all alone.

Breathe zeroes in on the girlish longing to be wholly made over—to be rescued from potentially lifelong ordinariness by a less fearful, more charismatic friend, a woman for whom everything is effortless. As such, Breathe belongs to a subset of films that couch female friendship’s complexity in the sensationalism of melodrama and horror. Amid tropes of codependent doppelgängers (Single White Female), covert attraction (Poison Ivy) and passionate violence (Heavenly Creatures), female friendship is esteemed and feared for its mutually transformative potential. In these films, women’s collusions tend to erect a protective barrier between the friends and whatever threatens their intimacy: male menace, familial duty, a small town, etc.

This exclusivity is key to the queerness and violence that often attend such onscreen friendships. As in romance narratives, mutual recognition draws friends closer by clipping them out of their surroundings. At its best, this isolation transforms intimacy into a thrilling secret; at its worst, it eradicates characters’ subsidiary support networks until one or both parties are terminally alone. In Anthony Minghella’s adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), girlfriend Marge articulates this double bind: “The thing with Dickie… it’s like the sun shines on you, and it’s glorious. And then he forgets you and it’s very, very cold.” In Breathe, too, Sarah’s initial warmth is so acute that it continues to compel Charlie, even, or especially, in its absence.

The switch takes place at a makeshift camp, set up by Charlie’s family friends to celebrate All Saint’s Day. Both girls struggle to define and enact the specificity of their bond to a broader audience; when Charlie reunites with an acquaintance and refers unthinkingly to Sarah as her “friend from class,” the perceived demotion triggers Sarah’s seismic shift. Until this point, laughter has been a pleasantly, if inexplicably, expansive response to a range of stimuli, the equally probable result of a Greek mythology lecture or a dirty joke. Now, Breathe stresses the dark side of this plasticity. Laughter isn’t just decontextualized by the film’s editing; it has an increasingly arbitrary relation to affect, such that Sarah laughing in one moment doesn’t protect Charlie from being slapped across the face by her in the next.

Sarah understands this; for all her ostensible breeziness, she’s as tactical as she is compulsive. She gets that the most potent mindfuck results not from outright rejection, but from the unpredictable vacillation between affection and abandonment. This, ultimately, is how Breathe deploys laughter: as a two-pronged instrument of intimacy, to encircle and alienate, to create and destroy.

Charlie is a prime target for her friend’s sophisticated manipulations. Against the backdrop of her parents’ separation(s), Breathe probes the parallels between mother/daughter modes of female doormattery. After taking a shower, Charlie gazes at her mother in the bathroom mirror. “Why do you always forgive him?” she asks. “I can’t do otherwise,” her mother replies. Left alone, Charlie watches herself drag a brush through her still-wet hair, wincing in tears as it snags. Why do we expose ourselves to pain, even when faced with the reflection of our own subjection? Because love can sustain an open wound. The film’s comparison of Charlie’s masochism to that of her mother highlights their mutual helplessness and the endurance of their desire; despite opportunities for retaliation or withdrawal, Charlie doesn’t seek reprieve from Sarah’s torment so much as long for their reconciliation.

Charlie’s love illuminates the ambidexterity of Sarah’s severity; her intensity is a powerful intoxicant, but this same relentlessness can veer in a darker direction. Either way, nothing is safe: not Charlie’s friendship to Victoire, her inconstant father’s access to their family, the handmade necklace Sarah finagles from Charlie’s mother and showily re-gifts to another girl at school, the secret of Charlie’s virginity, or the integrity of personal space. Sarah’s extended monologue in the film’s last act confirms her insatiable cruelty. It isn’t enough to desert Charlie, to smear her reputation, repeatedly luring her into and ejecting her from temporary ease; the opportunity to leave Charlie with the burden of blame for their estrangement is irresistible.

As Sarah sits on Charlie’s bed, retrieving the clothes she’d loaned months before, she unspools the story of their breakup. In it, the character of Charlie is selfish, judgmental and perpetually wounded. “You drive people crazy, then you act like a beaten dog.” Amid the handheld camera’s trembling, Charlie’s stillness draws air from the room. This is what the film tells us bedrooms and bathroom floors are for: being made over into your best self, and being dismantled beyond recognition. Two distinct laughs punctuate the climactic scene. First, in a version of the why do you make me so mad defense conventionally delivered by domestic abusers, Sarah laments Charlie’s role in her behavior: “You make me play the bad guy. It’s unbearable.” Charlie chuckles despite herself, and seizing on the gesture, Sarah presses on: “You think that’s funny? All the better.”

But laughter exists apart from what’s funny—or pleasurable, or even intentional. In “The Use Value of D. A. F. De Sade,” Georges Bataille admiringly describes “the excretion of unassimilable elements, which is another way of stating vulgarly that a burst of laughter is the only imaginable and terminal result […] of philosophical speculation.”[ii] The cruel laugh is the result of thinking that does not produce but excretes, leeching from the body as release without resolution.

Sarah tortures Charlie with her plans to move to Paris with Isa, her shiny new best friend. As she forecasts Charlie’s parochial future (a nearby college well within the orbit of her parents’ perpetual drama), she articulates the very fate Charlie briefly escaped through the amphetamine of their friendship. Abruptly, Charlie hurls herself at Sarah, who careens into the nightstand and onto the floor. Earlier in the film, Charlie overhears her mother confide to her aunt that her father’s behavior has become increasingly violent, although he hasn’t touched or hit her. This is the violence with which Breathe is most concerned: supple, ambient, but no less threatening for its immateriality. And in this sense, the spectacular ending seems to belong to a different film.

But when Sarah draws herself up from the carpet and lies back on Charlie’s bed, her groaning turns into a laughter that’s absurd, unnerving, indifferent to humor and opaquely nonverbal—as incongruous with catching a nightstand to the face as it is consistent with the film’s abiding grammar. It’s weird for her to laugh here, in the middle of their worst (and last) fight, and also utterly in keeping with Sarah’s imperviousness and the film’s ongoing traffic in hysterical laughter. In laughing while bleeding, Sarah refuses to recognize that Charlie has touched her, or that she ever could, and it’s this merry refusal that ultimately proves too much to bear; Sarah has the last laugh at the expense of her breath.