“Every face tells a story.” – Agnès Varda, Visages villages (2017)

Across many of her works, in her decades-long filmmaking career, Agnès Varda has searched for stories in people’s faces, histories embedded in the concrete textures of places, locations and architecture. Her films create topographies of the human experience, always—directly or otherwise—through a feminist lens. Her first feature, La Pointe Courte (1955), opens with a close-up of a piece of wood, its grooves containing stories of its age. Two early short films, Ô Saisons, Ô Châteaux and Du côté de la côte, commissioned by the French Tourist Office in 1958, embed both natural and manufactured locations with a sense of their individual human resonance. L’opéra-mouffe (1958) shows vignettes of Paris’s Latin Quarter through the eyes, and body, of a pregnant woman—perhaps Varda herself. In the more recent short Le Lion volatil (2003), Varda uses the sculpture of a bronze lion at the Place Denfert-Rochereau near her home on rue Daguerre in Paris to build a narrative, in which a woman is confused and influenced by her urban surroundings, that pays homage to France’s surrealist history. These films reflect Varda’s intimate attention to space around her, her desire to explore the world through its histories, artifacts and architectural scenery.

With her 12-minute cine-essay filmed for French television, Les dites cariatides (The So-Called Caryatids, 1984), Varda distills this attention through the feminine sculptures buried in the fabric of Parisian architecture. Varda acts as the unseen narrator, offering an overview of the history of the caryatids via the writings of Roman architect Vitruvius, who described them as modelled on perceived traitors captured in Greece during wartime: men were slain, and women were captured, then displayed in punishment in punishment as statues on public buildings. As Varda shapes it here, the caryatids are representations of enslaved women, idealized figures introduced not to honour real history, but to placate the desires of spiteful men.

As The So-Called Caryatids opens, the camera pans upwards on the body of a sculpture, past her delicately placed toes, a small piece of ruched cloth, her breasts. The title is revealed in frame as there is a cut to another sculpture, a woman with golden hair and bronze wet-drapery hanging below her waist. She holds a white flame above her head, as a lamp. As the title fades and the sculpture becomes illuminated by daylight, a man steps into the frame and stops next to her, striking a similar pose, before he walks, naked, into a public intersection. “On the street, a nude is more often in bronze than alive, in stone than in the flesh,” Varda proclaims in voiceover. And yet Varda chooses to show a nude body in the flesh, and it’s important that this body is masculine. This moment, with a touch of Varda’s tongue-in-cheek humour, points to how the nudity of women is socially readily accepted in public spaces (and in art, as the Guerrilla Girls pointed out), but the nudity of a man is unexpected. This opening also calls to mind another historical disparity: that women are often excluded from active participation in public spaces, where men are free to roam out in the open. When Charles Baudelaire and later Walter Benjamin wrote of the flâneur, they identified a distinctly male practice of the 19th and 20th centuries. Varda expands it, and she searches for and welcomes others.

Delving into this Parisian topography, Varda creates rhythm mostly through cuts, her languorous panning and still shots giving some relief to the caryatids’ paralysis. At a distance and in close-up, she films “women” who hold up balconies or the façades of buildings – all who do so without visibly bearing strain in their bodies or expressions.

Delving into this Parisian topography, Varda creates rhythm mostly through cuts, her languorous panning and still shots giving some relief to the caryatids’ paralysis.

A pair of mermaids pose outstretched, as though elegantly tumbling through water. Two angels lay across an arched doorway, their wings pressed against a building, each using a single arm to hold up a decorative frame. While they are anonymous and nameless, they are separated by their hairstyles, some in long plaits that caress their sides, some with loose curls around their faces and flower crowns, some with locks that flow away from their bodies. Some, perhaps mourning, have their faces covered by veils.

In capturing these statues, so often overlooked by the pedestrians who pass them every day, Varda creates an urban, architectural map built from lived trajectories, histories, fictions, truths. She invites us to wander as an inhabitant in their world, perhaps as Giuliana Bruno wanders through the tangible landscape of the cinema screen in her 2002 book Atlas of Emotion. Cinema, writes Bruno, is architectural practice that exists as a fluid space to be inhabited.[i] It allows women to practice flânerie, to gain ground against the flâneurs who had excluded them.[ii] While The So-Called Caryatids is not widely written about compared to some of Varda’s other works, it engages with much of her recognized thematic terrain. It exposes this publicly-buried history.[iii]

As Roman sculptures, these women—women floating somewhere between real and representation—are figures of desirable physical perfection. Created by male architects and builders, caryatids are the sculpted visions of man: although carrying a load they show no exertion, while male counterparts are atlases, their expressions betraying great effort. Men are strong, but women are docile. Varda thus makes it clear that the caryatids are part of an historical pattern that erases women’s contributions to society, and their humanity. She films stone women who hold up the façades of buildings or their balconies, women who bear the weight of streetlamps on their heads, all who do so without bearing strain in their bodies or expressions. By including images of women carrying boxes, engaged in social, capitalist, domestic labor, in Paris and Portugal where she has photographed them, Varda does not ignore women’s existence in the structure of patriarchy. In one shot, a woman airs bedclothes from a balcony between a pair of tranquil caryatids, as if the juxtaposition further emphasizes the invisible labour of women that has persisted throughout the centuries. This film is an architectural symphony, composed with a gentle, but unmistakable, political tenor.

The caryatid is, Varda narrates, only “a concept of woman in architecture.” A concept, not a reality. “A dream in stone,” Varda quotes Baudelaire’s poem “Beauty” published in The Flowers of Evil in 1857, the same decade many of the caryatids appeared. She reflects on this impossible expectation, recollecting Baudelaire’s struggle with reality amidst his desire for idealism. “Yesterday you were a goddess…today, you are a woman.” While this might be seen as a flaw, for Varda, all women with human flaws—that is, all women—are perfect.

To counter this impossible concept, Varda invites us to sing the voices of the caryatids. Of Varda’s fiction feature Le Bonheur (1965), a damning criticism of patriarchy, Carol Mavor writes that colour “is the voice, the timbre of the mostly silent women of the film.”[iv] Perhaps Varda makes a similar gesture in The So-Called Caryatids: she becomes the voice of these silent, invisible women. From the very beginning of her life as a filmmaker, in both documentary and fiction, Varda has searched spaces for the stories and voices buried within them. While her films are often open explorations of ideas, it is unquestionable that through them she follows her goal of depicting lives and voices that are otherwise excluded from the limelight.

While her films are often open explorations of ideas, it is unquestionable that through them she follows her goal of depicting lives and voices that are otherwise excluded from the limelight.

Like the faces she films, the city tells a story, and as she is a flâneuse, Varda is also, more notably, a glaneuse. In capturing the figures on building façades, Varda gleans other terrific sculptural detail, like the untouchable gilded bronze of clock faces and blocks of colour, and the everyday mechanisms of a city, in its traffic, its civilian activity, and the traces of human life so essential to its pulse. Perhaps her curiosity can be traced back to Varda’s brief time spent under the tutelage of Gaston Bachelard, that poet of spaces, to his phenomenological attunement to the world. Her camera observes residents leaning out their windows and cleaning a caryatid on their building, an angel standing three stories tall on rue Turbigo. Varda says, “No one knows who made her, or what she represents,” yet allows her to be seen on film.

As the film ends, Varda’s camera pans upwards to the vast stretches of Parisian roofs, dirty terracotta chimneys scattered across a blue-hued greyness of the city’s buildings, and its grim sky. It is a city of rooftops made famous, and largely defined on film, by the male eye. Varda reclaims the image, and the space, inviting us to linger in it and reaffirm its significance. She reclaims the rooftops for the woman’s perspective.[v] Varda is not only allowing these caryatids freedom in their environment; continuing the course set by her earlier films, she is redefining the city of Paris as belonging to women.

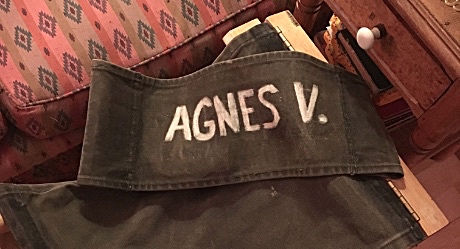

A few years prior to this experience of wandering through Paris, Varda noticed the living histories in the murals of Los Angeles, bringing them to the screen in Mur Murs (1980). Narrating from behind the camera, Varda declares murals as having a voice, as talking, murmuring. “Whether collective daydreams or personal visions, the walls tell of a city and its people.” Architecture speaks. It is something she has continued through to her most recent film, Visages villages, made with French street artist JR. Cinema speaks.

As part of her decades-long attention to voices of the unheard and her sympathies to making women visible, The So-Called Caryatids is a key work. “What would you say tonight, poor soul?” Varda wonders via Baudelaire, filming the silent sculptures of women.[vi] They are stone, of course, symbols of enslaved women that were surely voiceless. But through her wondering, and wandering, Varda gives them the voice of film. In an interview published by The Believer, Varda commented: “In all women there is something in revolt that is not expressed.”[vii] In tracing the stories and experiences of women and bringing them to light in everyday spaces, in architectural terrain, Varda has found a platform for this long-desired need.