In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released a report detailing the abuses and deaths of around 150,000 Indigenous children in residential schools in the settler state known as Canada.[i] While the numbers allow a glimpse of the “truth” of settler colonialism, the dialogue surrounding residential schools in both Canada and the United States remains stagnant and reeks of secrecy. The trans-continental project of assimilation through schooling has often been swept under shallow cultural and political narratives of reconciliation by a well-intentioned and overly-apologetic settler government. Two years prior to the report by the TRC, Jeff Barnaby (Mi’kmaq) directed Rhymes for Young Ghouls (2013). The film locates itself toward the end of the era of residential schooling, following a young woman, Aila, played by Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs (Mohawk), who deals drugs in order to pay a “truancy tax” and stay out of the local boarding school.

The film opens with quotations taken from an amendment to the Indian Act, which establishes the criminalization of Indigenous children who fail to attend boarding schools and the Indigenous parents who fail to send them: “truancy.” These quotations begin to tell a different story, despite what former Prime Minister Stephen Harper says about there being “no history of colonialism” in Canada.[ii] Regardless of the official fictionalization of Canada’s history, the film’s striking initial frames introduce the story of Aila and the fictional Red Crow Reserve boldly, declaring that residential schooling was no accident: such a phenomenon was a purposeful, legal system meant to eradicate the First Nations of Canada.

Regardless of the official fictionalization of Canada’s history, the film’s striking initial frames introduce the story of Aila and the fictional Red Crow Reserve boldly, declaring that residential schooling was no accident: such a phenomenon was a purposeful, legal system meant to eradicate the First Nations of Canada.

During the first seven minutes of the film, viewers are bombarded with depictions of graphic violence—drug addiction, alcoholism, police brutality, murder, suicide, slurs. That this sequence follows the quotations from the Indian Act does something that the TRC’s report could not. Flattening experiences and constructing residential schooling as an isolated event, a decontextualized apology and the numbers of a report are unable to depict genocide as a complex system of killing and assimilation, nor the extent of its reach into the lives of Native people. While these forms of violence are regarded by settlers as the inherent status of Native relations, Rhymes for Young Ghouls pushes viewers to come to terms with the severity of residential schools as a part of a project of genocide meant to “continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada.”[iii]

From the Western genre to docudramas, depictions of Native people as “broken” or constantly immersed in violent affairs have appeared and re-appeared without the context of the violence’s origins. The power of settler states like Canada relies on a type of colonial aphasia[iv] in which its own processes and histories of violence against Native people are rendered hidden and unspoken. Violence and injury done to Native bodies are visible only to the extent that they are depicted as discrete or isolated events. The spectacle of injury then serves as an additional reinforcement of settler power. Without understanding settler colonialism as a set of ongoing processes of making, the repetition of violence in Native spaces like the reserve becomes understood as an inherent condition of life instead of as a part of conquest and genocide. The reserve is thus constructed as a bounded space, rife with police presence, in order to surveil Native life and further fortify myths of Native people in constant conflict. As Eve Tuck (Unangax) has written on damage-centered research, “After the research team leaves, after the town meeting, after the news cameras have gone away, all we are left with is the damage.”[v] The damage, delinked from the structure of settler colonialism, becomes naturalized through its repetition in reports and cinematic portrayals.[vi] Rhymes for Young Ghouls redeploys this spotlight. Here, instead of positing an account of violence that takes place on the Red Crow Reserve as the basis of the myths of Native “brokenness”, Rhymes for Young Ghouls blossoms into a dynamic account of an intimate and perplexing form of care in the midst of violence.

The power of settler states like Canada relies on a type of colonial aphasia in which its own processes and histories of violence against Native people are rendered hidden and unspoken.

When Aila’s father Joseph is released from jail, after being framed for the death of a young Indigenous girl, he is adamant that Aila quit selling drugs. In the years of Joseph’s absence, Aila has maintained his drug business to pay her truancy tax to the police on the reserve. Her business is not easily condemned, as it has been constructed “intricately” over seven years and maintained to keep Aila out of the residential school, and to keep the household intact. This defense is much less about the role of drugs and much more about survival, and how gender functions as compelled labour.

Aila takes on the role of caretaker in her own mother’s physical absence; not only does she maintain her drug business to care for herself and her relatives, but she is forcibly assimilated into a sacrificial position. Her body functions as the locus of negotiation for the processes of and resistance to settlement. Non-native men on the reserve that attempt to violate her corporeal sovereignty, physically and sexually, simultaneously appear as repercussions for her male relatives’ snitching or stealing, and punishment for her perceived essence as a Native woman. As Audra Simpson (Mohawk) explains, “An Indian woman’s body in settler regimes such as the US, [and] Canada is loaded with meaning—signifying other political orders, land itself, of the dangerous possibility of reproducing Indian life and most dangerously, other political orders.”[vii] Simpson traces the Indian Act as an essential political manifestation of settlement in its’ redefinition of Native women’s socio-political status and thus, their children’s status as non-Native through sexual relations with white men. Considering the means through which settlement weaponizes kinship away from empowerment and toward the destruction of clans, much more is at stake for Aila while running a drug-dealing business, as her position as caretaker renders her culpable for the trauma of settlement.

Aila makes the transactions, but in doing so, is reminded by her grandfather’s friend Gisigu that in wartime some keep “moving with the dead piling up around our feet.” The verb “with” in “moving with the dead” enables an alternative kinship that exceeds the murderous entrapment of the settlement. As Aila works, she consults with two important women from the Red Crow Reserve—Ceres, whom Aila refers to as “grandma” and her biological mother, Anna. Moving motherhood away from death and trauma momentarily, we can consider Alexis P. Gumbs’ concept of “mothering” as a verb in the context of the Black feminist tradition. “Mothering” is something that marginalized women do; it is a form of care that establishes relation rather than a biological relation like “motherhood” that coerces care along axes of race and gender.[viii] Two distinct cinematic techniques arise in the intimate moments of Aila’s isolation with Anna and Ceres—moments of “mothering.” These techniques help viewers holistically come to terms with Aila’s motivations as a character and against readings of her as a receptacle of abuses of Canadian settlement.

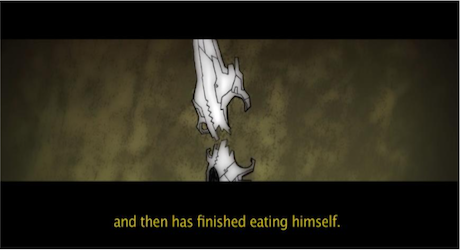

The first technique is animation. Animation is used when Aila is with Ceres, her “grandma” who provides her with drugs to sell. Ceres passes knowledge on to Aila through the traditional form of storytelling, sharing the story of the wolf and the mushroom, one in which a wolf hallucinates from hunger and eats Mi’kmaq children who appear as mushrooms. The wolf then feels so guilty that he continues to eat and devours himself. While this story may be interpreted with the wolf as a metaphor for the Canadian residential schooling system, representing the story through animation detaches the content from the rest of the film. That animation appears nowhere else in Rhymes for Young Ghouls may seem like a misstep but it can instead be read as a cinematic tool that enables oral tradition to appear in film, which has broader implications for potential representation than for the film itself. Breaking the limitations of images bound to the materiality of settler/linear time and space, the invocation of the story using animation locates its contents somewhere else and enhances storytelling in a way that challenges static representations of Indigenous cultural traditions and ways of life as solely enabled through the biopolitical control of settlement. Furthermore, the story of the wolf and the mushroom has stayed with Ceres, throughout and after her experience in boarding school, since her mother told it to her. “Your mother is telling it to you too,” says Ceres to Aila in her native language. The word “mother” serves a dualistic function as a reference to Aila’s biological mother who reappears later in the film as a guide, and pointing to the moments of mothering that Ceres is fostering with Aila through telling her the story and assisting her in staying out of the boarding school.

Breaking the limitations of images bound to the materiality of settler/linear time and space, the invocation of the story using animation locates its contents somewhere else and enhances storytelling in a way that challenges static representations of Indigenous cultural traditions and ways of life as solely enabled through the biopolitical control of settlement.

The second technique is a combination of camera focusing and costuming that may be labeled as the “visual afterlife.” This is used in the film to empower Aila and to help viewers see her mother, Anna, in physical death. Anna appears as not-dead in the cemetery where her body is buried, with her flesh discoloured and decaying, her voice carried by the sound of a heavy wind, and her face obscured by lighting, camera angle and focus. Such a depiction does not undermine the implication of Anna’s physical death or the violence that produced the encounter; instead, a meaningful spiritual relationship between Anna and Aila develops, one which transcends the physicality of death. This cinematic style articulates a resistance to the notion of time as linear. Anna appearing as not-dead resists the myth that the project of settlement in Canada is complete in destroying Indigenous ways of being. That Aila responds to her mother’s complaint that she never visits with “I don’t need to come here to see you” draws attention to the various ways that those of us targeted by settlement are always “moving with the dead.”

These two cinematic techniques not only enable a complex and dynamic story to be told about Native life—particularly Native motherhood—on a reserve, but they help us imagine futures outside settler “truths” and free from a so-called “reconciliation” that attempts to insulate settler states like Canada from responsibility for the ongoing genocide of First Nations and Indigenous peoples. Rhymes for Young Ghouls helps us think structurally. The films’ cinematic style blurs the lines between the material and immaterial and the boundaries of time, allowing us a deeper relationship between our relatives that are alive and our relatives that are dead. It is this “moving with the dead” that the film points towards—a sort of dreaming beyond a singular time, space or place that energizes Native women, as a part of a larger group of marginalized mothers, to do the work that keeps their communities together and thriving, despite everything.