In Miami, the struggle to stay above water is manifest. Model buildings are built to test hurricane force winds,[i] while defensive sea walls, high-capacity pumps, and stormwater drainage systems are installed in those areas most at risk.[ii] The menace of rising sea levels and extreme weather events is felt more concretely by some more than others: in a phenomenon dubbed “climate gentrification,” wealthy Miamians threaten to displace residents of traditionally working-class neighborhoods as they flee their waterfront properties to higher ground.[iii]

In Astra Taylor’s 2018 documentary What is Democracy?, emergency room doctors at Jackson Memorial—the largest hospital in Miami— diagnose another symptom of this inequality, wherein those who are financially vulnerable are at higher risk of injury. One of the doctors, Rishi Rattan, opines: “It’s not just the poverty here, it’s the disparity. It’s the extent of extreme richness, right next to extreme poverty.” Taylor asks: “If you could cure the social body what would you do?” On this the three physicians agree: education is the solution.

While the doctors are decisive, Taylor’s approach to the question of what plagues contemporary democracy—exemplified in both the documentary and her 2019 book, Democracy May Not Exist, but We’ll Miss It When It’s Gone—is not so definitive. The film’s examination is expansive—from ancient philosophy to Black Lives Matter—and the individuals she comes in contact with are far ranging: within a ten-minute span we visit Opportunity Threads, a worker-run sewing cooperative in North Carolina, and the Berkeley office of political theorist Wendy Brown. In this way, What is Democracy? makes its own claim for education as remedy; if there is any fix Taylor identifies, it’s for collective engagement over resignation.

Taylor is uniquely positioned to tackle the root of such widespread ill. A seasoned organizer, writer, and documentarian, she has investigated other similarly urgent and enduring questions: the role of the philosopher in modern culture (her 2008 film, Examined Life) and the socio-political implications of the internet (her 2014 book, The People’s Platform). Fittingly, cléo spoke with Taylor via e-mail about what ails us—and what’s to be done:

If you search “democracy” in Google images, you will be met with a litany of hands: in fists, whether held together, or reaching towards ballot boxes. What was your strongest visual association with democracy prior to making this film?

It’s hideous what comes up, isn’t it? I find all of that to be such an affront and a total aesthetic turn off. Indeed, looking back, part of what motivated me was a desire to transform my own associations with the word democracy. In fact, when I started out, “democracy” conjured precisely those sorts of tired visual tropes, which partly explains why I didn’t feel particularly excited about the term. Democracy struck me as mealy-mouthed and debased—something hollowed out and sold out. I valued words such as equality, liberation, socialism, and revolution more than democracy.

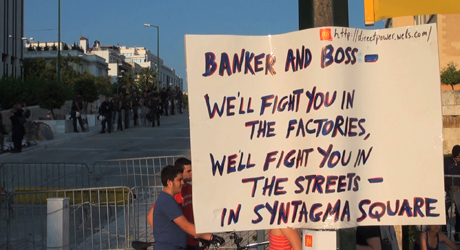

Nevertheless, on an intellectual level I knew democracy was an important concept, and also a potentially cinematically fruitful one. I wanted to investigate my own ambivalence and see if I could find a more authentic connection to the term. To do so, I knew I had to avoid certain clichés. So, the film doesn’t show people voting, there are no shots of the White House, it doesn’t end with a rousing protest and people interlocking arms to rousing music, there aren’t a lot of serious men in suits laying out procedural arguments, and so on.

Part of the challenge of representing democracy in any medium is that “the people,” the demos of democracy, is an abstraction. “The people” doesn’t just exist out there, the way a king or a prime minister does. Instead, “the people” is something inherently multifarious and conflicted. “The people” is not a crowd or a mob, though it does occasionally rise up and riot. It also transforms, it’s highly unstable. No wonder so many documentaries, even political ones, revert to individual stories and heroic David-vs-Goliath-style narratives. But I’ve just never been that drawn to character-driven story arcs. I’m more interested in the challenge of making an abstract concept, and an inherently collective one at that, the star of a film.

A number of events have taken place since you began this project that have changed the way many perceive the health of global democracy—notably, the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump. Did these events illustrate, or did they alter, your underlying thesis? How did they impact your approach to the film?

I first pitched the film to my producer Lea Marin, of the National Film Board of Canada, in 2013. By the time Brexit and Trump happened, we were neck deep in the project and those events served more as a confirmation of the relevance of the topic than a catalyst to shift course. In the end, I think those events meant I had to do less work to explain why I was interested in democracy—suddenly it was just obvious to people. Everyone can see that democracy is in crisis, which was not the case when I began. In my initial proposals I did a lot of explaining that I eventually left out. I thought I would have to do a lot more work setting up the problem and trying to communicate to the audience why I cared and why I was making the film and asking the question. That all turned out to be unnecessary.

How did you go about gathering subjects—both academics and laypeople—to ensure a more representative sample of the demos than the myopic pool of political pundits we’re accustomed to?

It’s a combination of an analytic approach and instinct. I structured the film and the cast because I wanted to make certain arguments—about history, capitalism, racism, and gender—but I also wanted to be open to learning and being surprised. So often I trusted my gut, reaching people through my political networks who I thought might know interesting folks or, just as often, stopping strangers who caught my eye and seeing if they’d be open to talking to me.

The academics are all people I had some kind of prior connection to. Silvia Federici, for example, is someone I know through social movements. Our conversation serves as a kind of spine for the film. We are standing together interpreting a fresco from the 1330s called “The Allegory of Good and Bad Government.” I knew I wanted the painting in the film, since it’s beautiful and evocative—it’s the first secular fresco, painted at a time when Italy was developing the tools of modern finance and amassing great wealth. I mentioned the painting to Silvia on the off chance she knew it and it turned out she had a reproduction of the main panel hanging in her living room in Brooklyn, so she was happy to travel to Siena to spend a day with me in front of the real thing.

I think your term “myopic” is correct. The problem with the usual suspects is that their vision is rather limited. There are so many things that privileged and powerful people cannot, or choose not to, perceive, which is why the oppressed and marginalized have, historically, expanded our democratic vision. In a wonderful essay called “Of the Ruling of Men” the historian W.E.B. DuBois writes about “excluded wisdom,” the wisdom of racialized people, women, children, and the working class that democracy needs. My hope is that the film, by paying tribute to this excluded wisdom, challenges the viewer’s conception of who an expert in democracy is. Maybe formerly incarcerated people and refugees and workers know more than an Ivy League academic or a professional politician. I think the movie actually approaches being a true meritocracy—people made the final cut not based on their official credentials but on whether what they said was insightful and resonant; not whether they had a degree, but whether they were wise.

There are so many things that privileged and powerful people cannot, or choose not to, perceive, which is why the oppressed and marginalized have, historically, expanded our democratic vision.

I will say that gender was key for me. Upper class white men dominate discussions of philosophy and democracy and I really believe that’s part of why the mainstream conversation is so uninspiring and inadequate. (For example, I was distressed to realize, that almost no women have authored general interest trade books on democracy, while some dude seems to drop a new title on the topic every week—reason enough for me to write my book.) Part of what I wanted to do was make a film that was feminist to its core without explicitly being about women’s issues. The movie features women of all ages and races and political orientations (in fact, some of the most troubling, reactionary comments come from young affluent white women). But I think the form of the film is feminist, in the sense that I tried to break with convention and put a kind of intellectual inquisitiveness and openness at the center, instead of performing what I see as this masculine stereotype of the authoritative intellectual director who knows all and is pulling the wool from the viewers’ eyes. I want to invite the audience to think, not do their thinking for them.

In one scene, Silvia Federici says that women have a “particular insight into democracy” because “women have never been befriended by democratic government.” Of course, saving democracy means saving an imperfect system, one that has historically excluded large parts of the demos. What role can contemporary feminism play in curing our afflicted system?

I think feminism has to be central, but again the question is: what do we mean by feminism? For me that does not mean more equal gender representation in a grossly unequal society. It doesn’t mean more women CEOs or cops or directors of big budget action movies. I think the women theorists in the film embody the kind of radical feminism I’m after, a feminism grounded in a material analysis that recognizes the intersection of gender and class (and other oppressions) and thus demands a reimagining and restructuring of the world at every level, from our interpersonal relationships to international trade deals.

Towards the beginning of the film, philosophy professor Eleni Perdikouri paraphrases Plato and Aristotle’s views that “a good life is one guaranteed by a good city.” I was drawn to the way the film portrayed different localities—particularly Athens, where ancient democratic landmarks exist parallel to bustling apartment complexes. Did these perspectives impact the way you and director of photography Maya Bankovic approached the locations in the film, as their own political entities?

Democracy, broken down to its etymological roots means the people, or demos, rule or hold power, kratos. So there are the questions of who the people are and how they rule. But there is also the question of where democracy happens. Where is the space of democracy? Is it the capitol building, the school, the workplace, the hospital, the bedroom?

Even in my previous film, Examined Life, I was very interested in place and how I could use cinema to reveal the fact that ideas are all around us, built into our environment and the infrastructure of everyday life. In this film, I wanted to expand that to also include a sense of history—we live amidst the accretion and wreckage and breakthrough of eras long past. Thus, the film draws on Plato’s Republic, arguably the founding text of Western political philosophy. That Socratic dialogue is set in the Port of Piraeus, which also happens to be one of the final locations the film visits. Twenty-five hundred years after Plato was there, the port remains a site of democratic contestation and struggle; it’s where I meet Salam Maghames, the 21-year-old refugee from Aleppo who is trying to get to Austria to reunite with her brother. The past is present in so many complex ways.

I think Maya and I were a great team; she is such a talented cinematographer. Maya is a master of beautiful vistas, of wide shots that show a whole tableau and she has this astonishing open-eyed patience; I was always pushing for more intimacy and immediacy. I think we struck the right balance, and one that suits the dialectical approach of the film: macro and micro, abstract and concrete, systemic and personal, intellectual and emotional. What I didn’t want was camerawork that was self-consciously arty, rarified, or in any way pretentious, especially given the heady subject matter. I wanted an aesthetic that was humble, direct, and inviting. No gratuitous drone shots allowed.

The film highlights that money begets influence in contemporary democracy (as you say in your book: “money, not ‘the many,’ rule”).[iv] To speak in cinematic tropes, is capitalism the born nemesis of a healthy social body?

Yes, there is no single hero in my narrative, but capitalism is definitely the primary villain. As Aristotle observed, rule of the many, by definition, means rule of the poor, since the poor always outnumber the rich. Capitalism is an economic system that concentrates wealth and power and so is, by definition, antithetical to democracy—it promotes rule of the few, or what the Greeks dubbed oligarchy. There was a time, last century, where a sort of functional truce was forged between capitalism and democracy, however problematically, but we’ve entered a new phase of capitalist development, with something meaner and more brazenly minoritarian emerging. At the same time, I wanted the film to give a critique of capitalism without reverting to jargon, tired rhetoric, or empty sloganeering. That’s partly why the metaphor of the social body is a recurring motif, because ultimately inequality, and the way capitalism divides people in order to exploit them, is a matter of life and death.

The film ends on a note of contemplation rather than resolution, and you write in the book that “democracy is a process that involves endless reassessment and renewal, not an endpoint we reach before taking a rest.”[v] What were you hoping audiences would take away from the film? Has their reaction differed from your expectations?

As an activist, I co-founded a group called the Debt Collective, which is essentially a union for debtors. The idea is that debt is an unused source of leverage for social change—if people come together, they can demand fairer terms or debt cancellation or even provision public goods including education and healthcare. As an organizer, I do a lot of calling people to action and mobilizing towards a specific goal. We launched the first student debt strike in 2015 and have won well over a billion dollars of debt cancellation for our members and paved the way for the student debt cancellation and free college proposals that are now part of the 2020 presidential contest in the United States.

I see my filmmaking and writing as something else, even if the themes occasionally overlap. Ultimately a film is a piece of art, not an organizing campaign. I want the film to do what I believe art does best—help shift perception and get people to understand the world and their place in it in a new light. It’s hard to be objective, but I think it’s working fairly well. Of course, What Is Democracy? is not everyone’s cup of tea, but my sense has been that audiences are more ready for an intellectual journey than many people in the film industry are inclined to believe. Thinking is pleasurable and people appreciate being addressed as thoughtful beings, instead of being pandered or condescended to or merely entertained. People often tell me they feel the film respects their intelligence, and they feel moved by that simple fact. But I’ll be honest, my expectations are really modest. I’m not making blockbusters over here, and I’m grateful anyone is paying attention.

To conclude, how—in the face of devastation from a changing climate, increasing inequality, and endemic racism and xenophobia—can we combat immobilizing despair?

People often ask me this. I think it’s the immobilizing part that’s the problem, more than the despair. Involvement is a kind of antidote to hopelessness, even if you are involved in a cause that is objectively unlikely to succeed. One can only combat immobilizing despair by mobilizing, I really believe that. Another classical definition of democracy is the capacity to do things together. The together is essential—we can only address the problems you name by working collectively. No one can advance democracy or rescue us from the devastations you name alone. There is a sort of democratic constitution we need to tap into at this moment—constitution not just in the usual political sense of a legal compact or code, but rather constitution in the sense of vitality and vigor, a democratic spirit we need to cultivate.

With this project I’ve been so immersed in the past. As a

result, I see how improbable every democratic victory was, how unlikely every

inch of social progress. Nothing was inevitable. That’s one reason why, as I

write in the coda of the book, I can’t help but feel hopelessness is kind of

trite. Who am I, sitting at my laptop or traveling with my film, to feel

overwhelmed? History brims with countless stories of people who fought for

change under much less auspicious circumstances than the conditions I’m

currently subject to. Climate change, and the suffering already being wrought

on this planet and our fellow beings, can indeed be overwhelming—and I think

it’s healthy to feel that grief and not just disavow or suppress it—but it also

offers what may be an incredible opportunity. Here, I’m with our fellow

Canadian Naomi Klein, who has brilliantly driven this point home. Change is

coming; business as usual cannot be sustained. It’s up to us whether that

change is more democratic or less, whether the fork in the road will lead us to

climate barbarism or something potentially better than the system we currently

live under. Crisis like so many of the words I’ve used here, also

comes from the ancient Greek. It was the turning point in an illness—death or

recovery, two stark alternatives. So here we are, amidst all these crises,

political, social, ecological. We have to be on the side of healing.