Harmony Korine continually recasts, perverts, and transforms a narrative that is held dear within the American imaginary—the coming-of-age story. From his work as the writer on Larry Clark’s Kids (1995), to his first film Gummo (1997), and now, with the bikini-clad wonder of Spring Breakers (2012), Korine offers explicit portraits of adolescent bodies behaving badly. The warped questing after love and AIDS of Kids, the cat-killing and euthanasia of Gummo, and now the drug and gun fueled self-discovery of Spring Breakers all reconfigure, in various degrees of iconoclasm, the notion of what it means to grow up in America. The interest of this piece is the disabled, sexual, radical bodies and flesh of Korine’s Gummo and Spring Breakers. It is through these bodies that Korine’s films articulate how people relate to one another outside of conventional structures of sociality (like the family or the workplace) and instead construct communities of offbeat misfits who form what critic Thomas Carl Wall called in reference to Gummo, a “confederacy of alterity.” Gummo and Spring Breakers reveal tightly knit troops of subjects who puncture the sacred dream of childhood innocence, proving themselves to be self-sufficient and self-actualizing characters who protect each other from the violence of the outside world. In turn, Korine’s films offer versions of the coming-of-age narrative that indulge in freakishness, revel in desiring young bodies, implicitly critique the consumerist and rape culture of contemporary neoliberal society, and thereby reshape the representation of onscreen intimacy and adolescence.

“I make films because I need to see them exist in a very specific way,” explains Korine in a recent interview with the New York Times Magazine, and indeed, the specificity of his subject matter and the temporal frenzy created through his editing offers up new ways of seeing. Set in Xenia, Ohio and filmed in Korine’s native Nashville, Tennessee with the help of French cinematographer Jean Yves Escoffier, Gummo is a hoarsely narrated account of adolescent life in a small community devastated by a tornado that claimed the town’s fathers. In Gummo, what can be seen is part spectacle, (a parade of bodies that are baldly and triumphantly coded as “other”), part empathy, and at times part envy for the characters’ quiet intimacies and unspoken social pacts. While Gummo’s dirty, queer, disabled, and fatherless children are held up by the film in a modern day white trash freak show, they are there neither to confirm nor deny fears of disability, of the impotence of the American Dream, nor of the frailty of the human body. Their mountain bikes and skateboards lead one through the poor Ohio town of Xenia, but despite their dirt, grime, and lack of direction, the distance and superiority of the spectator’s voyeurism cannot be sustained. While we look at the vulnerabilities and financial destitution of others we are confronted not with pity but with a distorted reflection of our own precarity—with the recognition of the bodily limits that make us human.

Gummo is a series of disconnected portraits of young frenetic bodies, some of which come into contact while others don’t. One of the bodies that Korine displays is of a nameless albino woman who speaks into the camera in a lonely-hearts-style interview. As techno beats emanate from the inside of her purple car, she sits cross-legged and coyly perched on its hood. Like a classic dating video, the teenager provides a physical inventory, listing off her hair and eye colour, weight, and height, smiling and laughing for the camera while she dances to her music. Describing herself as having blonde hair, blue eyes, and light skin, she adds: “I am considered, what you would call, an albino.” Although her extreme whiteness places her literally and figuratively beyond the pale of mainstream culture, she speaks confidently and comfortably into the camera about who and what she finds sexy. Of the 1980’s heartthrob Patrick Swayze, she swoons and divulges: “I love that man to death…I would pay money…to touch him.” Immediately following this moment the video camera with Korine behind it slips into the shot and is reflected off the car window. Always present, (and even joining the cast midway through the film as a drunk and rambling teen), Korine inserts his body into the frame as a way of reminding the viewer that the camera manipulates representations of desire just as much as it records them.

One of the final scenes of Gummo is of the film’s two bleach blonde nymphets, Dot (played by indie princess Chloë Sevigny) and Helen (Carisa Glucksman), in a backyard swimming pool with a young shirtless boy wearing pink fuzzy rabbit ears—the wandering queer playboy bunny whose presence serves as one of Gummo’s few structuring principles. Together the three teenagers splash and kiss while the non-diegetic sounds of Roy Orbinson’s “Crying” permeate the playful encounter. The unthreatening sexuality and impishness of this intimate scene is a precursor to the startlingly tender threesome near the end of Spring Breakers.

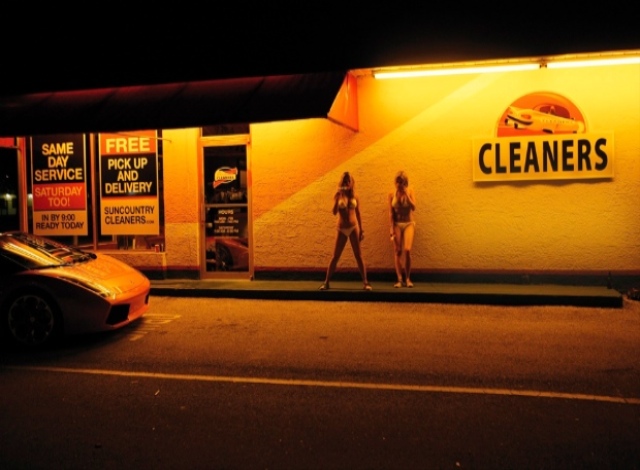

Without wanting to reduce the specificity of Korine’s texts to a coherent genealogy that tracks the continual loss of innocence and renders close-up the recurring failure of the American Dream, I will not trace all the moments of continuity between Gummo and Spring Breakers (in part because I would then be tempted to draw further connections to Nabokov’s Lolita, MTV, Browning’s Freaks, the films of Godard, Thelma & Louise, etc. and end up caught in the maelstrom of Korine’s incessant albeit beautiful referentiality). Instead, I will just say that Spring Breakers feels like a sunset-drenched middle-class version of Gummo insofar as it too is fixated by the potentially radical shapes that intimacy can take. In this instance, that shape is a wayward foursome of college girls who rob a local all-night diner to facilitate their dreams of escaping to Florida for the hedonistic American rite of passage, spring break. The spring breakers are played by Disney-franchise icons Selena Gomez, Vanessa Hudgens, Ashley Benson, and actress Rachel Korine, who is married to Harmony and has also appeared in Mister Lonely (2007) and Trash Humpers (2009). Often linked arm in arm, the four young women (Faith, Candy, Brit, and Cotty) are not reduced to pornographic girl-on-girl caricatures that the film’s title or opening scene of slow-motion beach party mayhem suggest. Despite the frat party atmosphere of spring break, their closeness with one another and their epic partying is not performed for the arousal of others but rather to indulge their own whims, appetites, and destructiveness.

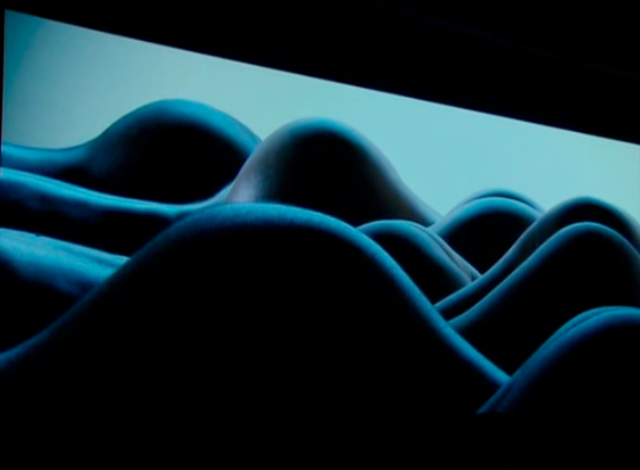

While the film is almost incantatory in its repetition of trite platitudes about living life to the fullest, finding one’s self, having the time of one’s life, and generally embracing the frantic call of carpe diem, the joie de vivre that buffs the glossy surface of the film is underpinned by an unrelenting death drive. James Franco’s character is a local Florida gangster and part-time rapper named Alien and is a visual and biographical refrain of Texan rapper Riff Raff. He bails the bikini and sneaker-wearing girls out of jail, and in one particularly resonant scene later in the film, shows off his guns, cash, and colognes to the only two “chickies” Candy (Hudgens) and Brit (Benson), who have remained with him post-spring break. Jumping around his bedroom yelling, “Look at my shiiiit!” and “This is the fuckin’ American Dream!” Alien is a perverse incarnation of Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby, who in attempting to impress his love interest Daisy Buchanan takes a pile of his linen and silk shirts and manically tosses them with great flourish one by one into a heap of texture and excess in front of her. Likewise, Alien giddily brandishes his wealth for Candy and Brit, yet they enact a surprising power reversal wherein they draw two of his guns on him, backing him up against the headboard of his king-sized money-covered bed. Unsure of the seriousness of their threats and epithets, Alien relinquishes the performance of his effusive gangster machismo and with equal parts fear and arousal, begins to perform double fellatio on the women’s fully loaded guns. This radical power play sets the tone for the future dynamics between the three, which ends up unfolding with reciprocity and mutual pleasure in a tender and sensuous threesome—notably marking the first sex we see any of the women engage in.

Something different, something intimate happens in Spring Breakers that is reminiscent of the pathos of Gummo, and if there is one thing that signals both films as radical and brilliant, it is a lack of the rape and abuse that accompanies many films where both women and sex are represented. The threat of rape is heavy in the context of wildly drunk and high half-nude college students, and yet our spring break heroines defy and diffuse this very threat with their dirty mouths, contorting limbs, and voracious sexuality. In an extended and epiphanic scene that is set to the diegetic ballad of Britney Spears’ “Everytime,” the characters dance a remarkably affecting ski-masked, gun-toting ballet of friendship and death drive that encapsulates their collective power and indelibly casts Korine as a filmmaker who gives shape to bodies that need to exist in a very specific way.