Profiles inherently require attempts at classification. In the case of cinema, directors, stars, and their films are most frequently fitted into tidy categories of genre and nationality in order to place them in relation to a broader, exterior context. It is an attempt to point to where they came from—their homes, as it were—in order to grapple with how they relate to our own. This tension is laced with ethnographic impulses and power structures (see: debates over the use of “World Cinema,” which suggests North America lies outside of this global qualifier), but also acts as an enzyme of sorts: with categorical expectations in place, films are pre-digested for consumption. The films of Athina Rachel Tsangari complicate this.

Though internationally recognized as a cornerstone of the new—and now struggling—movement in Greek cinema, Tsangari resists neat categorization. Born in Aspra Spitia, Greece, her family moved to Athens when she was five, from which she decamped at the age of 18 for Austin, Texas. She remained there until her mid-30s, before returning to Greece’s capital. Home, as she discusses below, was never merely one place. Moreover, Tsangari isn’t only a director, she also produces her own films and those of the likes of Yorgos Lanthimos and Richard Linklater. In addition, she started the avant-garde showcase Cinematexas International Short Film Festival in Austin, founded the production company Haos Film, lectures at her alma mater the University of Texas, and can currently be seen in Before Midnight (which reunited her with Linklater after her small part in his 1991 film Slacker). Just as her diverse curriculum vitae isn’t easy to peg, her films don’t neatly fit into one genre, and they actively resist definitive readings as part of a broader national identity.

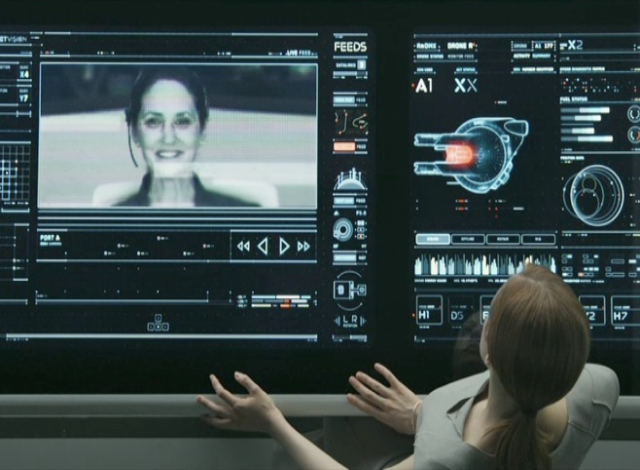

Her first short, Fit (1994), was made during her time in Texas. The film offers an anthropological-satirical examination of the daily life of Lizzie (Lizzie Curry Martinez), during which the young woman’s mundane actions are narrated by a David Attenborough-esque voice. Infused with the sounds of cicadas, reality takes on a surreal quality as the animal world fuses with the human. (A reminder that we are animals, too, after all.) Fit fixates on re-occurring themes of biology and ethnography. Six years later, Tsangari made her first feature, The Slow Business of Going, which sprung from her thesis film at the University of Texas. Following a pseudo-cyborg who travels the world to record moments with strangers, the film interrogates the homogeneity of modern space and its impact on memory. It was with her sophomore feature, Attenberg, that Tsangari was launched into the international spotlight after the film’s premiere at the Venice Film Festival in 2010. Made on the cusp of the Greek economic collapse, Attenberg became a crucial film in the contemporary Greek cinema—a point Tsangari takes issue with. Her latest work, The Capsule, diverges stylistically from what Tsangari has done before and overtly explores the limits of genre and gender expectations.

Having just completed her most recent project—“I wish I could talk about it, but I can’t, it hasn’t been announced,” she told us from Athens—Tsangari spoke to us about privileging biology over psychology in her films, why she dislikes being labelled as part of a “national cinema” as much as being called a “woman filmmaker,” and working with Linklater in Greece.

cléo: I want to talk about the use of physical space in your films. In The Slow Business of Going there’s the homogeneous space in the hotel rooms; Spyros taking on the qualities of his town in Attenberg; the gothic house that the women in The Capsule occupy. What is it about the relationship between space and people that intrigues you?

Athina Rachel Tsangari: This is very difficult for me to talk about, because when I’m creating a character, space isn’t just something that surrounds or encloses him or her—it’s a character itself. In my first films, space had to do with the question of naturalism or realism in cinema, and whether you choose to position your characters in the “real world.” I’ve been shying away from full-on realism until now in the new film I’m preparing, because there’s always a science-fiction element of space; it’s abstracted. The Slow Business of Going was a very personal film, dealing with being a professional observer. And in a way, in all the films I do, this idea of observing life as biology—or geography or ethnography—is something I’m very interested in. In Slow Business, I shot in several cities across the world, shot all the spaces in between on Super 8 as an observer, but the fictional episodes were all spaces that could be interchangeable. All those hotel rooms could be anywhere; the spaces are all interchangeable because all those chain hotels look the same if you’re in Tokyo, Mexico City, Prague, Athens, or New York. And I was very interested in that, the Ikea colonization of space. That film was made before the Ikea era, but that was the idea: hotels being the first model of an Ikea form of habitation and multiplication of the human experience. In Attenberg, I chose Aspra Spitia not so much because it was my childhood town—I was only there until I was five—but because it was important to me that this space was “colonized” in the 1960s by a French mega-company. It was a company town that did not belong to the Greek landscape or culture, and in a way was projecting Greece into the future. When I was growing up there, it was as if I was living in the future, this European future that Greece was seeking in the mid-1970s. Then, when I went back to shoot 20 years later, it was a Greece that was crumbling and nostalgic for a future that she never achieved. It was a political decision to shoot there, not a personal or nostalgic one. It wasn’t a return home in that sense. In The Capsule, it was a specific decision to shoot in one of the few Greek gothic houses from the 18th century. The house belonged to a woman who was a revolutionary and a ship merchant—the family didn’t have boys—which was quite extraordinary for the times. This made it very important for me to shoot there, as in the film it is a house where women are educated on what they are supposed to be in a male-centric society like Greece. I seek methods to get at the essence of the characters through archetypal spaces. Like the way it’s structured in ancient Greek tragedy, which is an important influence on how I construct my settings and characters.

cléo: I always come back to the term “body talk” when thinking of your films, the idea of communication that isn’t through language. And especially women’s bodies.

ART: This is the problem with you critics, you have some reading on our intention and we don’t know what to say! [Laughs] I guess it comes from the question of why has speech taken centre stage in cinema. In the 1960s and 1970s, the use of the human body was so advanced, then in the 1980s all of this was obliterated. The things I did in Attenberg were not things I invented—I studied it in Godard and Antonioni, I saw it in Minelli, Hawkes, Lubitsch. Now we have to revert to explaining why we are doing this. Cinema has become much more conservative than it was 80 years ago. Character, space, and speech were an organized entity that was fused together and you didn’t have to explain or apologize for it. And now you have to talk about it in some discourse that was resolved 80 years ago! Take Vertov, take Eisenstein—this was popular cinema at the time. Now we have to explain why narrative cinema can work not necessarily through dialogue, how bodies can speak. And I see this as a problematic devolving. I have nothing against Aristotelian ethics in cinema: identification and catharsis. Perfect. But there’s this mode of filmmaking that has been so consolidated that one feels trapped. It has something to do with a strong conservatism in setting expectations quite low for what an audience can take. As always, cinema is a reflection of politics, and this conservatism is showing—it’s as if we went back to the 1950s, nothing is supposed to upset the status quo. Though I sense we might be living the end of the “new 1950s” and we’re about to enter something new. I tend to be interested in biology and politics more than “psychology.” I think there’s something about easy psychology that has ruined cinema. And it’s not that I’m trying to make difficult cinema, but there are ways to be more open and adventurous in the way you codify and signify.

cléo: A language that you have to work for, in a way.

ART: Exactly, and you shouldn’t apologize for taking genre, which is a code, and bastardizing it. This is something that many people are afraid to do. How many directors do you know who go for it unapologetically? Take David Lynch, for example. He’s experiencing life fully, and reflecting it in cinema fully. And I respond to that because I see a revolutionary anarchy in it. Breaking rules and being personal, combining formalism with emotion—this is something I’m trying to negotiate.

cléo: The lines between borders, limits, and spaces tend to collapse in your films—especially the worlds of animals and human—which then highlights how civilization is a construction. Would you agree?

ART: When you watch Attenberg, it’s very much about the limits between animals and humans. Or in Slow Business, Petra is this kind of cyborg. And in The Capsule it’s very much about the threshold between women and creatures who are in the process of being born. At the same time, I think this question of borders is represented formally in my interest in genre. I don’t want to be apologetic about it, I do it in a very instinctual way—and it might not be in a way that is according to the rules. I think this interest in genre is something that is almost forbidden in female cinema. If you are a woman you do human stories, chick films, romantic comedies—there’s a limit in what we are expected to do. Which is something I find very sad. I don’t want to be limited by what women are “assigned” to do, in life and cinema.

cléo: I’m glad you brought up the question of expectations of female directors. How do you respond to this gendered qualifier? Do you see anything productive in it?

ART: No, absolutely not. It’s not something that usually happens with male directors, and it’s a big burden. And it can be a ghetto. If you are a woman director then there are expectations, from producers to the audience, of what you should be good at because of your gender. For instance, in the film industry, with very few exceptions in the last 120 years, you have to prove that you can do something outside of what is expected. Why can’t a woman make an action film, a war film? Why is it that Kathryn Bigelow can’t do what she does without getting all this shit about making “male” movies? It’s unfair, and after 120 years we should be a little more advanced. It is a problem with national cinema too. That if you are a “national” director you should say specific things about your country. For me, Attenberg was a universal story about a girl growing up, not so much about Greece in the crisis, or other things that construct this artificial buzz about Greek cinema. There’s a colonialism in cinema which takes form in the way you are expected to make certain things—if you are a woman, Greek, African, Indian etc filmmaker. There’s an unconscious, or conscious prejudice embedded in the audience’s expectations, and the critics. It creates a feudalism in cinema, and I resent that. After Attenberg, I did The Capsule, which was a genre I was very interested in exploring and getting my hands dirty with: gothic horror, the vampire film. And I reckon some people were like, “What does it have to do with Greek cinema?”

cléo: The limitations of “national cinema” are something I’m very interested in. Increasingly, funding is global in scale, so the idea of one country making a film doesn’t happen in the same way it once did. Is there even a productive value in calling something “national cinema”?

ART: No. Look at Greece, the national Greek broadcaster was shut down overnight by the government, and that was our main source of funding. This was the only non-private channel that was supporting Greek cinema and television. The Greek Film Centre is fighting against a slow death, due to lack of public funds. So any Greek film that is being made right now is made for literally nothing, or through European funding. National cinema then is something that relies on the interpretation of international funders. Dogtooth and Attenberg, those were different because they were made before the collapse of our country. Their content and production strategy were accountable to us alone. Now we have to export Greek cinema as a pseudo movement—you see what Europe wants to fund and have to live up to that. Which are basically films about the Greek crisis. And I don’t want to make a film about the fucking Greek crisis in the way Europe, or the world, thinks it should be made.

cléo: It’s this pattern of shining a light on one national cinema, canonizing it, and then moving on to the next. For instance, a few years ago it was Iranian cinema.

ART: Yes. And Greek cinema is something that is very complex. It’s not a constricted movement; all the films are very different. You can’t really talk about a “school.” I feel very uncomfortable being part of a trend. It’s a form of self-colonizing and limits what cinema could witness and restage, as each of us experiences the soul and decline of our country in different ways. You can’t homogenize that. This also limits what gets shown. If it’s not what is expected of a “movement,” it might never get shown. It’s all about stereotyping minorities in cinema.

cléo: What are your feelings about the Toronto International Film Festival selecting Athens for their City to City program this year?

ART: I’m very happy that Athens was chosen, but I don’t know what films are programmed. In the end, the representation of a country depends on a programmer’s specific selection, no?

cléo: Right, like what you were saying about female filmmakers, it’s about reducing things to what you expect.

ART: To tell you the truth, I haven’t experienced that because I’ve always done what I wanted. I’m also producing my own films. We have a company with fellow filmmakers, Haos Film.

cléo: Was choosing to produce then out of necessity, a choice, or a mix of both?

ART: It’s something that I really love to do. It affords you the freedom to do things the way you want to do them. We had the freedom to do the stuff we did, with my films and [Dogtooth director] Yorgos Lanthimos’ films. The idea of making films outside of state funding was something that just wasn’t happening. The American model of independent filmmaking doesn’t really happen over here. But that way of making films was very empowering to us. That was the revolution of Greek cinema: we did things with very little money, without expecting approval from anyone.

cléo: Your first short film, Fit, was made in the US. Would you consider making a film in the US again?

ART: Yes, I am preparing a film that I plan to shoot in the US. Not necessarily Texas, where I lived for a big part of my adulthood, but I yearn to do something in my other native language, English. I was in the States from 19 to 35. So working in my adoptive native language is something that is equally natural and essential to me.

cléo: Romantic comedies keep coming up, which I want to talk about in terms of Before Midnight.

ART: I think Richard Linklater, who has been a mentor and an example to me since Slacker, has a way of being formalist and personal and political all at once. He doesn’t do a single film that he doesn’t absolutely believe in. All of his films are extremely political and human—and that is very rare. It’s important to be a cartographer of the world around you, and he does that. To see a film shot in Greece, which was a universal story but fused with Greek cinema, was very moving to all of us.

cléo: And we’re back to this idea of fusion again! And in Before Midnight your character, Ariadni, talks about colonization; colonizing your partner as a form of love.

ART: Yes, it’s a question of opposites with that couple. They don’t quite fit each other, but in the end, they have surrendered, despite themselves, to unconditional love. Ariadni and Stefanos have a game that they play of being antagonistic, but in the end they adore each other. That is what I’m after in the cinema I’m trying to do. Things, people, ideas, styles that don’t really fit together come to meet each other in the middle. Formalism and drama; observation and immersion; humor and tragedy. But somehow, these things can belong in the same world, and the same frame.