My fascination with nuns in cinema began in high school. I attended a Montreal all-girls Catholic academy and did little socializing outside the institute’s walls. The school had once served as the residence of Canada’s Governor General, until Loyalist rebels burned down the building in 1849, forcing the Governor to flee with his family. Following this incident, the property briefly became a hotel before being purchased by the Congrégation de Notre-Dame in 1854 and reopening as a boarding school for girls. [i]

To this day, a life-sized figure of the Virgin Mary welcomes students in the main lobby—above her hangs a long, thick rope. According to tales passed down by older girls, a guest of the former hotel hanged herself with this very rope in the aftermath of a torrid love affair. Ghost stories naturally materialized in a historic building where people had succumbed to disease, drowning and possible suicide; students’ adolescent imaginations were consumed with fantasy, and the bloody, titillating legends sliced through the mundanity of our lives.

Along with these lurid stories, my own teenage fantasies were shaped by the religious shame that permeated my education. By the time I became a student the nuns were no longer teaching, so it was the sisters of fiction, rather than real life, who came to occupy my hormonally charged dream world. In this environment, I was drawn to religious dramas like Black Narcissus (1947), The Nun’s Story (1959) and The Bells of Saint Mary’s (1945); in place of any tangible outlet for my new and confusing erotic feelings, I clung to narratives about all-woman environments bound by Catholic restrictiveness and wrought with temptation.

This obsession ultimately led to my discovery of nunsploitation cinema, an exploitation sub-genre that capitalizes on religious taboos by exploring the darker, erotic side of convent life. Although nunsploitation peaked in the 1970s, it belongs to a much longer legacy of stories spawned from rumours about the mysterious life of nuns. As early as 1353, Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron includes the tale of a handsome young man who pretends to be mute so he can work within the otherwise forbidden walls of a convent. The beautiful cloistered women grow increasingly bold, eventually using the protagonist to explore their carnal curiosity. A more sombre tone permeates later novels like La Religieuse (1796), which focuses on the unwilling imprisonment of young women within strict religious orders and the humiliations they suffer at the hands of superiors. Nunsploitation films were a natural extension of these motifs, combining freer depictions of sex on screen in the 1970s with an enduring, if heteronormative, fascination with the lives and desires of women bereft of men.

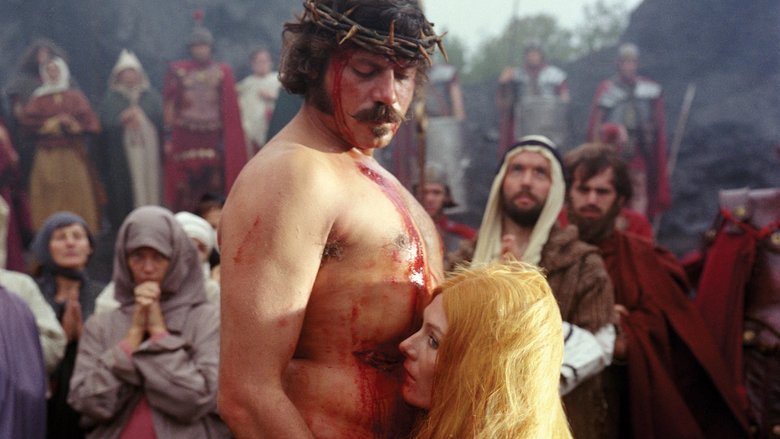

Released in 1971, Ken Russell’s The Devils served as the bridge between the tortured, but still mostly chaste, religious Hollywood dramas of the 1940s and 50s and the softcore pornography of nunsploitation. Inspired by a supposed incident of mass hysteria at a convent in the French village of Loudun in 1634, The Devils centers on Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), a priest accused of witchcraft by a jealous and spiteful nun after he rebuffs her advances (Sister Jeanne, played by Vanessa Redgrave). Rated X and banned in multiple countries, the film builds to an orgiastic scene featuring naked sisters indulging their every ecstatic pleasure. Both the British censors and Warner Brothers demanded cuts to this sequence, specifically a moment known as the “Rape of Christ,” in which the delirious nuns desecrate a life-sized figure of Christ on the cross, accompanied by a vivid and unsettling jazz score. This controversial scene is not one of demonic possession, as Sister Jeanne later claims—rather, it’s the culmination of her efforts to take down Father Grandier. After inciting the frenzy, she blames the priest for it, knowing he will be prosecuted by the church.

In the throes of my awkward adolescence, I related to Sister Jeanne and her Catholic shame. Like her, I yearned for sex and power but was besieged by loneliness. Flawed and destructive, the frustrated nun is never able to derive fulfilment from her devotion to Jesus. Given my own cloistered circumstances, Jeanne’s eroticized conflation of Father Grandier with Jesus Christ struck me as natural, and a dream sequence in which she licks blood off of the priest’s body felt like an obvious convergence of desire and repression. It was only in dreams (and daydreams) like Jeanne’s that I could act out my own erotic fantasies, and even those moments were weighed down by a deep sense that I was betraying the moral order of my religious environment. Somehow, the fusion of pain and pleasure made “sinful” desires feel more acceptable—the punishment was built into the act itself.

Somehow, the fusion of pain and pleasure made “sinful” desires feel more acceptable—the punishment was built into the act itself.

Sadomasochistic imagery—often relating to themes of demonic possession, mass hysteria and sexual frenzy—is inseparable from nunsploitation. Torturing the female body is paramount, be it through fasting, self-flagellation or punishment. The bodies in question are often young, unblemished and “virginal,” and the characters inflicting the violence take gleeful pleasure in corrupting them. Jesus Franco’s Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun (1977) is especially representative of this motif: its loose narrative follows Maria (Susan Hemingway), a teenage virgin forced into a cultish convent where she is humiliated and tortured. In one scene, Maria is tied up in chains by other novice sisters while the mother superior looks on with a barely concealed grin, reclining suggestively on a red velvet chaise longue. There is an unmistakable sensuality to the mother superior’s movements as she approaches the bound novice and accuses her of being possessed, and an unspoken understanding that Maria’s only crime is being desirable.

Nunsploitation films often seem to equate female sexuality with humanity’s fall from grace at the hands of Eve in the Garden of Eden, and watching beautiful bodies get smeared with blood, beaten with rose thorns and broken down can feel like witnessing an act of vengeance for a millennia-old imagined infraction. One of Love Letters of a Portuguese Nun’s most representative images is that of Maria’s naked body wrapped in a thorny vine—as her persecutor tightens the vine’s grip around her torso, the camera lingers on a trail of blood oozing down her side. But instead of revealing any insights into Catholicism or the characters, this moment simply indulges lecherous viewers hungry for sex and blood.

Love Letters is pure exploitation, favouring titillation over empathy and embracing a sadistic gaze without subverting it. Conversely, Norifumi Suzuki’s School of the Holy Beast (1974) employs many of the same images and themes as a means of highlighting the intimacy that can emerge between girls and women isolated from the world. Unlike many nunsploitation films, School of the Holy Beast is set in an era contemporary with its release (the 1970s). It opens with a montage of Maya (Yumi Takigawa) revelling in the pleasures of the secular world: hockey, hot dogs and hot sex. In fact, she’s squeezing the most out of life before committing herself to a convent, begging the question: why would a free and independent young woman willingly impose such restrictions on herself? In true melodramatic form, it turns out that Maya is on a quest to investigate her mother’s mysterious death at the convent, which occurred two decades earlier, and find out who her father is.

School of the Holy Beast opens with a montage of Maya (Yumi Takigawa) revelling in the pleasures of the secular world: hockey, hot dogs and hot sex.

Short on religiosity, School of the Holy Beast features incredible tableaus of punishment and self-flagellation that feel rooted in a deeper church corruption. Young and impressionable novices are victimized by church leaders who inflict punishment for minor infractions despite their own major crimes against God. Referencing the Holocaust and the atomic bomb for good measure, Suzuki depicts the church as a microcosm of society—an institution in which power corrupts absolutely and salvation is more a question of opportunity than morality.

As a young woman, I connected with the film’s display of solidarity against authority, as well as its portrayal of the intense connections spawned by the strange artificiality of a hyper-feminine environment ruled by men. The close female friendships of my teens and early twenties, while not necessarily sexual, were invariably imbued with a frenzied passion akin to an unrequited crush. Such relationships were forged from shared opposition to teachers and dogma more than any common interests—a closeness bred, above all else, from imagined acts of transgression.

Richly sensual, School of the Holy Beast balances its violent imagery with portraits of deep intimacy between women. In one of the most beautifully framed sex scenes I’ve witnessed in cinema, two young nuns escape to the convent’s greenhouse to make love among the flowers. The sequence is vibrantly edited and fully invested in feminine pleasure: cunnilingus is simulated through expressionistic intercuts of an extreme close-up of a nun’s tongue and fingers moving suggestively. In contrast to the barely concealed bloodlust of the older sisters during an earlier scene (in which two young nuns are forced to beat each other with whips), a shared understanding and respect is found among the novices in stolen looks and tender touches.

Erotic master Walerian Borowczyk took nunsploitation to even more intimate depths with his 1978 feature Behind Convent Walls (although, for some purists, this picture exists on the peripheries of the genre, more closely aligned with The Devils than with outright exploitation flicks like Love Letters). Like School of the Holy Beast, Behind Convent Walls eschews devils and demons—its abuses are institutional rather than explicitly satanic. While in no way absolving the characters of their cruelty, this choice allows for a far more nuanced critique of the power of the church.

Like School of the Holy Beast, Behind Convent Walls eschews devils and demons—its abuses are institutional rather than explicitly satanic.

Borowczyk’s film expresses a deep loneliness, both erotic and spiritual, and reveals the ways in which the forced isolation of the convent creates a charged sense of alienation that, in turn, can lead to a disconnect from reality and an impulse towards self-immolation. Among the novices, Sister Veronica (Marina Pierro) yearns for a close relationship with Jesus. She does yoga naked in her room, believing the physical act of prayer to be integral to her relationship with God. When interrupted mid-session by a horrified older nun, Veronica claims that the abrupt intrusion has chased away the spirit of Jesus, revealing a growing psychological instability. She proceeds to isolate herself from her sisters, focusing her erotic impulses on the attainment of a spiritual miracle. Veronica makes a crown of thorny red roses for the statue of the Virgin Mary, only to violently prick herself with them later on. In the aftermath of this wilful flagellation, her full-blown hysteria becomes evident when she claims to have been blessed by stigmata. Pierro’s performance in this scene conveys delusion more than fraudulence—a desperate plea for spiritual connection rather than a malicious lie.

In its examination of loneliness, Behind Convent Walls focuses on fleeting social interactions and the camaraderie built out of shared frustrations. The intimacy portrayed is not only physical but emotional; discretion and companionship are required to survive psychologically. As if in a prison drama, the novices rely on each other for services and goods that are otherwise unavailable. One of the nuns, a skilled painter, is commissioned to paint erotic etchings of men and receives a request to paint a beautiful portrait of Christ’s face on a smooth, elegant dildo carved by another sister. Later, painted dildo in hand and alone in her room, the young woman uses a mirror to watch herself masturbate, focusing on the water-coloured face of her divine lover. The sexual act feels more liberating than shameful, a brief escape from the lonely repression of the nun’s daily life.

Behind Convent Walls focuses on sexual and spiritual self-exploration far more than most nunsploitation films; depictions of romantic liaisons and friendship are balanced almost scene-for-scene with shots of young women left alone in their rooms with nothing but a bible and their own body. Borowczyk’s preference for soft-focus camera work is particularly resonant during these scenes: his emphasis on the textures and sensations of skin, hair and clothing evokes a sensual experience in stark contrast with the far harsher and more violent outside world which eventually invades the lonely convent.

While not quite a horror film, Behind Convent Walls turns towards darkness in its final act as church authorities enter the narrative. In her book on French cinematic extremism, Alexandra West writes about religious-themed horror and how it “reinforces the patriarchal world order by suggesting that chaos and temptation will lead to humans’ eventual downfall.”[ii] But Borowczyk, radically, treats the repression and self-protectionism of the church as the real enemy. When faced with a murderous sister who poisons the mother superior, the authorities respond with secrecy, preferring to uphold and maintain the existing power structure rather than examine any institutional wrongdoing. Ultimately, the will of the church supersedes the mental and spiritual health of the convent’s inhabitants, many of whom are imprisoned there for financial reasons, as opposed to a deliberate desire to devote their lives to Christ.

My introduction to nunsploitation coincided with my adolescent sexual awakening. Films exploring the painful intersection of desire and intense loneliness offered an escape—a kind of perverted refuge for my complicated feelings and lascivious imagination. Within the confines of Catholicism, these movies not only mirrored aspects of my own experience—they also created a universe in which imagination held as much transgressive power as sex. But as much as I related to the genre’s thorny depictions of sexuality, I felt an even more powerful connection to the ways in which works like The Devils and Behind Convent Walls, in particular, blurred the lines between religious devotion and erotic desire. Rather than divide the physical and spiritual aspects of sex, these films connected them.