After a thirteen-year hiatus, filmmaker Leos Carax returns with Holy Motors (2012), a kaleidoscopic dawn-to-dusk journey through Paris following the chameleon-like figure known only as Monsieur Oscar (frequent Carax collaborator, Denis Lavant). Oscar is an actor-for-hire, commissioned by a series of unknown clientele to perform as an array of characters, playing out vignettes on the streets of the city. A businessman with a burden, an old woman forgotten by the world, a brutal assassin, a helpless victim—Monsieur Oscar is able to traverse gender, genre, and mortality. But for whom are these performances? Where are the cameras? Monsieur Oscar has grown weary of his work. If the “beauty of the act” is in the eye of the beholder, he wonders, what happens when there is no more beholder?

Oscar’s lament is the central paradox of performance. It is an art that is undeniably and irrevocably of the body. This is the thesis of French theatre actor Constant Coquelin, as he defends his line of work as an art form worthy of reverence:

“The poet has for his material, words; the sculptor, marble or bronze; the painter, colors [sic] and canvas; the musician, sounds: but the actor is his own material. To exhibit a thought, an image, a human portrait, he works upon himself. He is his own piano, he strikes his own strings, he moulds himself like wet clay, he paints himself!” [i]

The actor is both artist and material. Though bound by the body, the actor pushes the limits of the flesh; enacting a transfiguration of sorts. Holy Motors stages Monsieur Oscar’s transfigurations as literal. Inside a cavernous white limousine-cum-dressing room, he moulds his body into new forms through make-up, costume, comportment and countenance. To take on the assassin persona, he paints the blank canvas of his shaved head and body with prosthetic scars and airbrushed grime. To become a homeless old woman, he adopts her extreme posture, gripping a cane and stooping at a nearly 90-degree angle. For the unruly, troll-esque Merde (a character previously glimpsed in Carax’s segment of the 2008 anthology Tokyo!), Oscar undergoes a process requiring a wig, fake fingernails, a cataract contact lens in one eye, and (for Lavant as much as Oscar) a prosthetic penis.

The tragedy of Coquelin’s art is that it is ephemeral. While the poet, the sculptor, the painter and the musician can be outlived by their works, the actor is once again limited by the body. Theatre acting is tied to time and place, and requires an audience who will freely suspend disbelief for the duration of a performance. Thus the actor can leave no physical trace of their life’s work. With death comes the destruction of the original work of art.

However, Coquelin’s writing on this subject pre-dates the first public screening of the motion picture by nearly 15 years. In 1895, the Lumière brothers unveiled their cinématographe films to an astounded audience in Paris. On the cusp of late modernity, it was a time when empirical evidence was thought to be unassailable, and this new technology thrived. Carax pays tribute to this history, bookending Holy Motors with an image that is almost incongruous to the hallucinogenic visuals that fill Monsieur Oscar’s day—an extract of an 1890’s-era Étienne-Jules Marey film of a walking nude male figure. Of course, Marey’s pursuit was not of art, but of scientific observation; cinephotography as a means of recording and studying the mechanics of motility—hands gesturing, muscles flexing, physiological and ethnographic studies of men and women and children in motion, birds in flight, crawling insects, etc. The history of acting on film is ostensibly a history of bodies on film.

Film technology eventually evolved from “pictures in motion” as an objective means of recording reality into the “motion picture” as a mode of entertainment and artistry. Film had the ability to preserve the actor’s art, imprinting his image onto celluloid. Coquelin himself briefly enjoyed this privilege, starring in his only film role as the titular character in Clément Maurice’s silent short Cyrano de Bergerac (France, 1900). Artists may die but the trace of their work survives, in (to borrow a turn-of-phrase from André Bazin) a kind of mummified state. In this regard, film projection is a strange act of resurrection. In Holy Motors, Monsieur Oscar is hired to perform as the assassin, hunting down his unsuspecting target (also Lavant, playing opposite himself). When Oscar-as-assassin kills Oscar-as-victim, the assassin sets about transforming his doppelganger in his own image—but this time through a mutilation of flesh, creating scars using a knife as opposed to prostheses. But no matter, as death and disfigurement are transcended by film. Though a mortally wounded Oscar stumbles back to his vehicle, once inside he is revealed to be unscathed.

Celluloid does suffer limits similar to that of the body. For the film strip is not the art object, but a piece of raw material. That is, it is merely a component of a finished work of art. The “performance” of a film (unlike traditional art or photography) is durational—the film experience can only occur within a prefixed timeframe. This has been a significant topic of debate concerning film preservation and restoration. To preserve film as a work of art, one has to preserve a system of relations that exist between the film strip, the projection technology, and a screening space. Of course, without an audience to fill that screen space, there is no performance—if Hamlet soliloquies to an empty theatre, does he really make a sound?

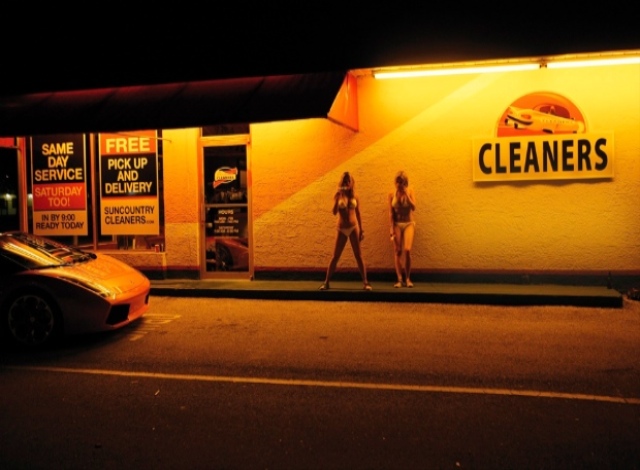

And what of the digital? Celluloid shares the limitations of the body, and it itself can be thought of as a body—it has corporeality, weight, tactility. Digital film, on the other hand, is characterized by lightness and weightlessness (says Oscar, “[the cameras] became smaller than our heads. Now you can’t see them at all”). Digital acting is very much in the same vein: a loss of presence and corporeality. Holy Motors tackles this in one of Oscar’s earliest appointments, which requires him to take part in a motion capture sequence. His “costume” is a spandex black bodysuit and covered with white reflective markers, some of which supplant the lines and crags of Lavant’s distinctive face. As he exits the white limousine his driver (Edith Scob) can’t help but giggle at his strange attire. His appearance may seem ridiculous in the light of day, but deep within the belly of the motion capture studio, Oscar gains a sinuous quality. Inside the all-black studio, an off-screen voice directs Oscar’s performance. With the aid of non-descript props, he shoots at unseen targets, fights unseen enemies, all for an unseen audience.

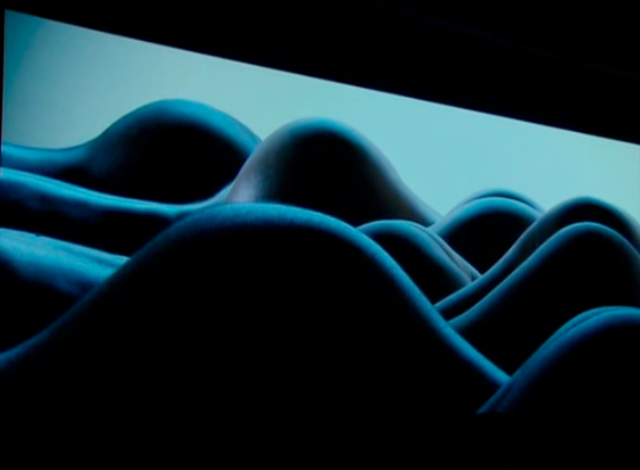

The vignette concludes with one of the film’s eeriest interactions. A mechanical door inside the mo-cap studio slides open and a statuesque blonde woman in a red motion capture bodysuit (Zlata) strides out with alien-like grace. She is able to contort her body into impossible shapes. As Oscar mimics her serpentine behaviour, they join together in an erotic embrace. While Oscar and his companion writhe and moan, their images are captured by the studio’s invisible digital cameras. On a computer interface, skin and musculature are digitally ripped from the actors’ bones in an act of oddly benign violence. Computer generated likenesses replace their writhing forms, transfigured into reptilian creatures fucking against a digitally rendered mise-en-scène. An obscene eulogy to the death of celluloid; to flesh and blood. The physical, corporeal “beauty of the act” is effaced by a digital image, many times removed from the body.

“I miss the cameras,” Oscar later admits to an associate. For if an actor gives a performance and no one seems to be watching, can it really be said to exist?