“I love you. I love you. I really love you. I love you.”

Carol White (Julianne Moore) stares into a mirror, repeating this phrase to her reflection in the final shot of Todd Haynes’s 1995 film Safe. This dénouement comes as Carol’s final offensive blow against the debilitating and unexplained “environmental illness” that has suddenly rendered her immune system ineffective against airborne toxins. The disease manifests as a series of escalating symptoms: a trip on the freeway causes a massive coughing fit; a chemical perm at a beauty salon triggers a nosebleed; a dry-cleaner induces a seizure. When her doctors are unable to find a medical explanation for her condition, Carol decides to leave the comfortable home she shares with her husband (Xander Berkeley) and stepson (Chauncey Leopardi), seeking out a holistic cure at Wrenwood, a health retreat that espouses mental well-being—self-love and acceptance—as the only route to physical wellness.

Moore’s performance as the demure late-1980s suburban housewife is strikingly sedate, delivering her dialogue in breathy tones that barely register above a whisper and dressing exclusively in understated pastels. Our first proper glimpse of Carol is of her face peeking over her husband’s shoulder as they have sex after a night out, her expression betraying a vacant resignation. This is one of several moments in the film in which she is contained and repressed by the spaces she occupies. In an extreme wide shot of Carol working in the garden, she is dwarfed by her San Fernando Valley mansion, a setting that is clearly the product of her husband’s wealth and success as a businessman. Inside the house, her muted style of dress is echoed by her home’s decor. She blends into her surroundings, as though she could evaporate at any moment.

From this description, it may be tempting to read Carol’s journey of spiritual awakening as one of empowerment, in which she breaks free of her stifling home life and enters a world wholly of her own making. And certainly, this analysis initially seems supported by the narrative. Such a reading, however, would ignore the class privilege at work in Haynes’s ultimately critical film. Specifically, the dangerous ways upper-middle-class self-involvement and delusion can be mistaken for radical self-actualization and empowerment. Carol goes from homemaking to the misguided “reality-making” of positive thinking—an ideological trap just as insidious as the one from which she escaped.

Carol’s withdrawn demeanour is less a result of subjugation than a by-product of her affluent complacency. While her spaces appear to constrain her, she is nevertheless complicit in her relatively comfortable life. Behind her diffidence lies a deep-seated need for control over her environment. This not only includes strict command over the elements within her home, but also involves keeping undesirable elements out. When Carol’s stepson Rory recites a current events essay about the Los Angeles gang wars over the dinner table, Carol is visibly disturbed:

Carol: Why’s it have to be so gory?

Rory: Gory! That’s how it really is!

Carol’s privilege is so entrenched as to be unwilling—or, perhaps, unable—to acknowledge a world so far removed from her own. At the start of the film, the mistaken delivery of a pair of black couches is enough to raise Carol’s voice from a whisper to an exasperated sigh—they simply do not go with anything in the house! In an essay for Reverse Shot, Genevieve Yue notes the arrival of the couches as so offensive to Carol’s orderly life, it marks the moment her illness begins to show noticeable symptoms—as though her highly sheltered existence has been invaded by a toxic foreign body, which manifests as an actual, physical ailment.

The panic and confusion of the AIDS epidemic looms over Haynes’s vision of the late 1980s; the onset of unusual symptoms and the lack of viable treatment options are darkly paralleled by Carol’s environmental sickness. The 1987 setting situates Safe on the cusp of the formation of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) and the San Francisco Model of therapy and treatment. Carol’s retreat to Wrenwood is an ineffectual counterpoint to a period characterized by the rise of AIDS activism. The model for change offered by groups like ACT UP is one of communal power. Group meetings, sit-ins staged at FDA headquarters, and peaceful protests in front of the Reagan White House brought together ailing bodies exercising collective action. Though Carol White also finds refuge with a group of similarly afflicted individuals, their method is one of collective inaction.

Thus, Carol’s retreat to Wrenwood is not a story of a woman breaking away from a world of repression and control, but retreating further into it. Wrenwood bills itself as a “safe haven for troubled times” that encourages its residents to focus their feelings inward—an extreme form of the insularity that Carol already suffers. Haynes is not subtle with his misgivings about this form of positive thinking philosophy. Indeed, early on a line of throwaway dialogue between a pair of cursory characters reveals his distaste for the empty tautologies of self-help: “[The book] is about how to own your own life. Because it’s like, what he’s saying is we don’t really own our own lives.” HIV-positive Wrenwood founder Peter Dunning (Peter Friedman) promises a cure for “troubled times” through strict rules of conduct: modest dress, no smoking, no drinking, no recreational drug use, no sex, silent meals…all of which speak to a thinly-veiled religious conservativism embedded in the centre’s New Age mantra: “we are one with the power that created us, we are safe, and all is well in our world.” Group meetings play out as revival sermons, in which the affable Dunning assures that the positive energies created by Wrenwood’s residents are able to change the world. At a later meeting, he confesses that he no longer keeps up with current events due to the media’s “fatalistic, negative attitude” adversely affecting his health. In her 2009 book Bright-Sided, Barbara Ehrenreich adroitly admonishes such a mindset:

The advice that you must change your environment—for example, by eliminating negative people and news—is an admission that there may in fact be a “real world” out there that is utterly unaffected by our wishes. In the face of this terrifying possibility, the only “positive” response is to withdraw into one’s own carefully constructed world of constant approval and affirmation, nice news, and smiling people.[i]

This is yet another instance of self-involved insularity masquerading as self-awareness. Rather than deal with a world outside of one’s control, the only practical solution is to ignore it, effectively cutting oneself off from reality.

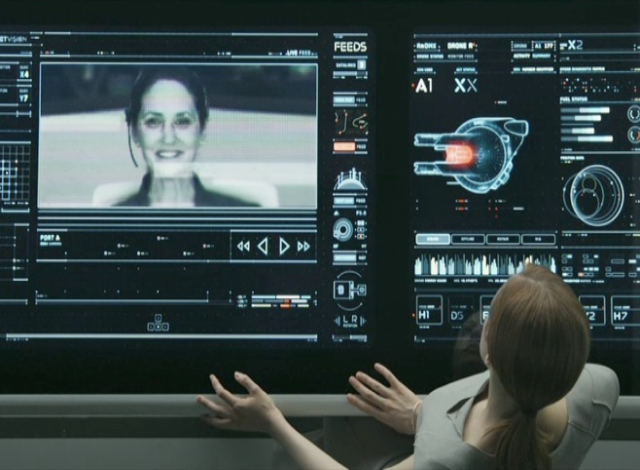

Returning to the final scene in which Carol gazes at herself in a mirror (which translates onscreen as peering into the camera), her proclamation of self-love is not, in fact, a moment of triumph against a likely psychosomatic illness. Despite instructions to “forgive herself” and “love herself,” and despite efforts to maintain a toxic-free environment (by moving into a small, hermetically sealed porcelain bubble on Wrenwood’s grounds), Carol’s condition has worsened. Her reflection belies her exhaustion: sunken eyes, emaciated form, sallow and bruised skin. If her disease is a manifestation of the emptiness of her experience as a housewife, the cure she chases is simply another empty experience. Sealed off from the world, in a claustrophobic space with barren white walls, all that’s left is the image of a sad, pitiable woman, trapped within her own limited purview.