For all their glossy futurism, female cyborg stories overwhelmingly pivot on the immemorial horror of rape. Whether such films and TV shows allegorize radical social upheaval or contemplate the mysteries of human consciousness, rape scenes inevitably lurk within their narratives. Sexual assault plots pair frequently enough with women’s bodies onscreen, but when those bodies are also liminal–figured as not human or adjacent to human—the threat of rape is nearly inescapable.

Sexual assault plots pair frequently enough with women’s bodies onscreen, but when those bodies are also liminal–figured as not human or adjacent to human—the threat of rape is nearly inescapable.

Knowing this doesn’t keep one from hoping otherwise—if anything, my wish, as a viewer and critic, for onscreen rape not to happen is as powerful as my conviction that it will. What matters to me, then, is how the work in question will handle, absorb, defend, eroticize, or complicate, rather than simply perpetuate or reject, rape as narrative cliché. Alex Garland’s directorial debut Ex Machina (2015), a film about assessing the consciousness of a compellingly humanoid cyborg, doesn’t just acknowledge this cliché, it promotes penetrability to an arm of its Turing test—such that who or what can fuck, or get fucked, replaces “human vs. robot” as the film’s central taxonomy.

Ex Machina opens with reedy programmer Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson) learning he’s won an office lottery for a weeklong stay at his company’s headquarters to work one-on-one with reclusive founder Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac). The company, Blue Book, is a software firm made popular by its development of a Google-like search engine and Nathan’s wunderkind reputation. Caleb is spirited by helicopter to a secluded research-slash-residential compound, where Nathan surprises him with the opportunity to evaluate his latest project: Ava (Alicia Vikander).

What follows is organized according to the conceit of the Turing test, after Alan Turing’s proposition that a human interlocutor use natural language conversation to evaluate a machine’s capacity to exhibit human-like intelligence.[i] The film presents seven episodes in the form of numbered “sessions,” where each session consists of Caleb conversing with Ava, followed by a debriefing with Nathan. Though the post-session conversations are markedly less formal, set over sushi or beers instead of through plate glass, the data gathered between Nathan and Caleb pushes them increasingly apart, while Caleb’s meetings with Ava appear to bring them closer, transforming their dynamic from test administrator/test subject to intimate co-conspirators.

Ex Machina inherits its dual fixations on verisimilitude and assessment from a long tradition of films about artificial intelligence, most notably Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982). Blade Runner’s machinic replicants differ from humans based on their engagement with the Voight-Kampff machine, which poses emotionally charged questions in the manner of an empathy test. Like a polygraph, the Voight-Kampff is administered through verbal interrogation, but ultimately measures bodily response. While it helps to say the right answer, to successfully “pass” (even temporarily, as might a replicant with false consciousness) human authenticity must manifest in the body.

Ex Machina resumes this study of human criteria, but uses the competitive dynamic between ambitious loner Caleb and his idol/employer to turn this question back on the questioner: what qualifies a human to be sufficiently human to assess supple, authentic, non-algorithmic humanness? Caleb handles his first debrief with Nathan like an oral exam, declaring his hots for “high-level abstraction”–but instead of outstripping Caleb’s intellect Nathan dismisses intellect altogether, pressing the programmer to simply “feel” toward Ava, in order to consider whether and how she feels back. “How do you feel about her?” he asks. “Nothing analytical.”

“I feel that she’s fucking amazing,” Caleb eventually admits. Nathan is satisfied, Caleb passes his first test, and the two clink beers, toasting the homosociality proposed when Caleb first arrived (“Can we just be two guys? Just Nathan and Caleb.”). While the performative arrangement of just two guys is impossible given their power dynamic, there’s something true here, too. The film’s protracted climax will smooth any superficial difference between them, any sense that benign, well-intentioned Caleb is passably heroic compared to unrepentant tech bro Nathan. In death, they’re equally fucked.

Like the compound itself, highly designed yet organically integrated, Vikander’s Ava is a composite form. Circuitry emits soft blue light from her translucent torso and bald “skull.” Opaque metallic netting around her pelvis and across her chest and upper arms approximates a sort of swimsuit. Her hands and face are enfleshed and thus expressive, as familiar as the motorized purrs of her movements are foreign. In Session 3, she surprises Caleb by changing into women’s clothing–specifically, into the outfit she would want to wear if they were to leave the facility together for “a date.” In a sequence of actions, images, and sounds that will repeat significantly in the film’s ending, Ava asks Caleb to wait with his eyes closed as she deliberates before a full closet, then emerges in a floral dress, knit stockings and a pixie-cut brown wig. Kneeling behind the glass, she asks whether he thinks about her at night when they’re apart.

In Affect and Artificial Intelligence, Elizabeth A. Wilson reinterprets Turing’s central question (i.e., could you make a machine that would have feelings like you and I do?) as “less an engineering query than […] a provocation about whether it is conceptually feasible to coassemble affect and machinery. When we contemplate the possibility of machines with feelings […] What kinds of human-computer interaction do we wish for?”[ii] Ex Machina answers Wilson’s question with a sequence in which “coassembly” is definitively gendered, and “wishing” takes the form of physical desire.

Late at night, after Session 4, we see Caleb taking a shower as Nathan works on his punching bag. Caleb’s eyes cut sideways under the water’s spray, cuing the image of Ava outdoors on a cliff. We’ve seen this same imagery in the session just prior, when Caleb told Ava a thinly veiled AI allegory called “Mary in the Black-and-White Room.” Caleb’s story suggests that “Mary” feels she is real until she experiences a world outside of her box—a world in colour. To illustrate this encounter between lack of consciousness and the rich real world, the movie interposes black-and-white footage of Ava at the edge of a forested cliff. She looks at the water below, then glances up and back at the camera, as if intruded on.

It’s possible to read this monochrome footage as expressive of Ava’s perspective, her wish for escape–but, crucially, these images are always Caleb’s. This is wholly his fantasy—initially of Ava’s longing (for freedom), but eventually, when he inserts himself into the picture, of his own. The film cuts wordlessly between the two men’s liaisons, real and imagined: Nathan with his assistant Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno), who stands by with a towel during his workout, and Caleb with dream Ava on the black-and-white cliff. Caleb’s reverie peaks in an imagined kiss, while Nathan turns to regard Kyoko, taking her hand to his face before fucking her up against the wall.

Ex Machina harks back, beyond the relatively narrow province of AI, to all manner of tragedies of warm, vivid affection for something inanimate or composed, where the strength of that affection has the power to animate its object.[iii] But Caleb never quite gets there. He’s indignant that Ava isn’t free, but only insofar as she requires a modicum of liberty to freely choose him. He imagines them together in an open outdoor space, as if a physical cage is the only measure of captivity.

To fuck the thing that might be a woman is not an arbitrary desire; rather, it’s linked precisely to that thing’s interstitial status. It’s no fun to fuck something that’s already, or only, an object–it has to show its human face through feminized comportment first. Onscreen collisions between ontological assessment and sexual coercion date back to Blade Runner’s Deckard raping replicant Rachael at the moment they both question her humanity, reinforcing the notion that the only certain method of android testing is to interrogate the body.

To fuck the thing that might be a woman is not an arbitrary desire; rather, it’s linked precisely to that thing’s interstitial status.

Earlier, when Caleb voiced his distrust of Ava’s seemingly flirtatious behavior, Nathan fell back on redirection: “To answer your real question, you bet she can fuck.” Ava’s body can both be penetrated (via an orifice where a vaginal canal might organically exist) and sense pleasure (via “nerves” that convey sensation data). The argument ended in an enigmatic bit of armchair art criticism in front of Nathan’s original Jackson Pollock No. 5. Drunk and soliloquizing, Nathan suggests that Pollock “let his mind go blank and his hand go where it wanted to,” finding an artistic zenith between deliberation and randomness. In one moment, he argues that Pollock wouldn’t have made art had he analyzed and telegraphed every brushstroke; in the next, he’s patting Caleb on the back: “There’s my guy, there’s my buddy, who thinks before he opens his mouth.” As much as Nathan, and Garland’s film, want to imagine the radical potential of intuition and immediacy and the limitations of logic, both remain firmly lodged within the framework of one versus the other, with logic always a step ahead–save for one profound exception: Kyoko.

Ex Machina is a captivity narrative, so it presses inevitably toward Ava’s escape. But even before Caleb reveals the contents of Nathan’s Bluebeardian bedroom closets, it’s obvious that Ava’s not the only captive. From the moment Kyoko materializes to serve Caleb coffee in stilettos, one suspects she’s not so much highly trained as programmed; the “striptease” in which she peels back the skin at her cheekbone and rib, confirming that she, too, is one of Nathan’s rough drafts, is arguably more spectacular than informative. But this, like all of Kyoko’s appearances onscreen, compels speculation. When Caleb dreams of her flayed eyes and examines himself in the bathroom mirror, he probes his eye socket, looks inside his mouth and slices his forearm with a razor, spreading the skin to measure his depth—to question the body. The film cuts to Kyoko watching a monitor in what looks like a reverse-shot of Caleb staring into the mirror, though this is never confirmed with a shot from her point of view.

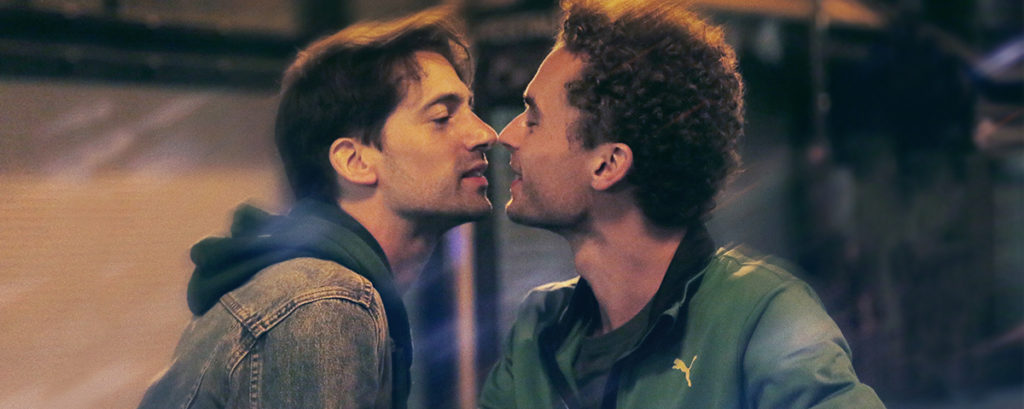

All these minor mysteries converge in Ex Machina’s most vital scene: Ava and Kyoko’s interaction in the hall. After Ava escapes her unit, she and Kyoko ostensibly share an encounter marked by proximity and micro-movement. We see their faces close together, Ava’s lips moving in a manner consistent with speech, her fingers tapping Kyoko’s arm, her hand taking Kyoko’s hand. It looks like the conspiratorial onset of a coup. Yet, like the earlier shot of Kyoko observing the monitor, this frame is formally evasive. The scene isolates the two AIs’ eyes and lips, cuts without clear motivation and withholds any clarifying dialogue (as the film has withheld language from Kyoko all along), thus depicting the film’s most important encounter as something we can witness but never fully understand. We can certainly suppose the content of their contact, and the nature of the relationship that contextualizes it–but, arguably, that’s all we can do.

Much of Ex Machina’s criticism has hinged on whether it’s a feminist revenge parable or an objectifying robot fantasy, but both readings threaten to flatten the complexity that we, like Caleb, are asked to feel without explaining. Ex Machina will, eventually, close its previously begun loops: after sliding a knife into Nathan’s back, Kyoko will cup his face in her hand in a spooky simulation of how he held and studied her face before he fucked her by his gym bag–the very scene the film telegraphed the moment Kyoko appeared onscreen. And Ava will again ask Caleb to wait for her, as she selects skin and clothes and hair, this time from Nathan’s closeted prototypes, and this time, without coming back.

But the moment in the hallway, in its partiality and mysteriousness, has no earlier model. Amid all the film’s unmaskings and sexual clichés, this, the mutual recognition between Ava and Kyoko, is the film’s greatest accomplishment: the true singularity.

Amid all the film’s unmaskings and sexual clichés, this, the mutual recognition between Ava and Kyoko, is the film’s greatest accomplishment: the true singularity.