Claire Denis’ latest film Let the Sunshine In, which follows the failed attempts at finding love by a middle-aged woman (tour de force Juliette Binoche), has been dubbed the “most empathic, heartfelt film of [Denis’] illustrious career.”[i] On account of its more tender subject matter, it’s also being hailed by some as a departure for the director who is better known for exploring topics that are typically less warm or “sentimental”: from post-colonialism (Chocolat; White Material), to suicide (Beau Travail), to rape (Bastards), to pure bloodlust (Trouble Every Day). The film also feels like a departure given its relative abundance of dialogue in comparison with her previous works. Yet this is something of a superficial dismissal of a complex auteur, especially when it comes to her exploration of desire.

Above all, Denis is known for the texture of her images (shot by frequent collaborator, the cinematographer Agnès Godard) which capture the fluidity of physical forms, rendering bodily movements into a complex lexicon that transcends the verbal. Because of this, Denis’ films often favour a radical present where the immediacy of communication isn’t based in linear dialogue, but rather extends far beyond the verbal, exploding common notions of time. In this way, Let the Sunshine In feels like a call back to one of Denis’ most undervalued works, Friday Night. Released in 2002 and based on the novel of the same name by Emmanuèle Bernheim, the film sometimes feels semi-forgotten, an outlier in her body of more “difficult” work. Like Let the Sunshine In, Friday Night is vulnerable to dismissive critiques that harbour a sexist resistance to taking matters of the heart seriously, especially those of women over the age of 30. And yet, Friday Night remains one of my favourite Denis films in its portrayal of sensuality that’s based in a disruption of linear time.

Similarly to Let the Sunshine In, Friday Night follows the sexual desires of a Parisian woman, Laure (Valérie Lemercier). Set over the course of one night, the film begins as Laure is packing up her apartment to move in with her boyfriend (who remains unseen in the film and whose existence thus functions primarily as a conceptual stand-in for monogamy). She leaves her apartment and finds herself stuck in a tangle of traffic, as the metro workers have gone on strike (oh-so-perfectly French). Stalled both literally in her car and figuratively as she waits to move forward with her relationship, in this state of limbo she encounters Jean (Vincent Lindon), who needs a ride. They eventually spend the night together. Like Denis’ latest, Friday Night was also seen as a departure for the director upon its release. As Judith Mayne writes on the 2002 film, “There are elements in [Friday Night] that we have never seen before in a Denis film, from the use of the dissolves to create subjectivity to the use of playful animation to imagine the lettering on a car […] and it is a resolutely sunny by the standards of Denis’ other work.”[ii] But like Let the Sunshine In, “it nonetheless explores the desires and movements that lie beneath […]a woman’s consciousness.”[iii]

Where the twinned films differ is in how they upend linear time in favour of a radical present. In Let the Sunshine In, this is accomplished through repetition of dialogue. The film is based on Roland Barthes’ 1977 book The Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, a structuralist examination of love following from the principle that “the lover is not to be reduced to a simple symptomal subject, but rather that we hear in his voice what is ‘unreal,’ i.e., intractable.”[iv] In plainer terms: love is a many splendid thing but the quest to experience it, and therein define it, only reveals time and again its ever-fleeting, intangible quality. The script (co-written by Christine Angot and Denis) renders nearly every conversation circular, so most scenes retread the same laments of Binoche’s character—fitting, given that the source material comes from one of the most famous semioticians preoccupied with the function, and failures, of language. The results are both comical and frustrating, but ultimately produce the suggestion that discussing love verbally is nothing short of a fool’s errand. Words don’t have the capacity to express the nebulous albeit common condition of being in love.

Friday Night embarks on a similar project though in an entirely different mode: with limited dialogue, Denis constructs a world where desire unfolds in a radical present. There is no past or sense of what’s to come (sexual innuendo fully intended), only what is in the moment. This is achieved on a narrative level, but also, and more evocatively, through the use of an elliptical editing process, cross-fades, dissolves and fragmented close-ups. Narratively, the film is set in the milieu of civic disruption:[v] the metro strike renders the familiar city of Paris new, in that the usual societal rules—don’t get into a car with strangers, for instance—don’t apply. Even before this element of the story is inserted (via a diegetic radio broadcast), Denis positions the city in a literal new light by opening the film with a series of shots of Parisian rooftops. But these are not the sunny versions that hang in a doctor’s waiting room: she shoots them at dusk, as the city moves from day to night, hinting at how the film will take place in a state of flux.

It’s in this “other” Paris that Laure is introduced, waiting for the morning when she will leave her apartment to begin a new life of cohabitation with her boyfriend. Like the dusk that is falling. outside her window, she too exists in a state of limbo, waiting for the next phase to take shape. She finishes packing her boxes and sorting her books and clothes (choosing to keep a red skirt with a sensuous slit up the side), bathes and leaves her apartment to go to meet friends for dinner. But this “forward” movement in the plot is quickly stalled, as Laure immediately becomes stuck in traffic. Her conundrum is more than geographical:, she can move neither forward nor backward physically in the bumper-to-bumper congestion, but she also appears to be disconcerted by her impending relocation, though by now she has irrevocably packed up her old life.

Up to this point in the film, time has ticked by slowly but surely for Laure, and the sequence of the shots have also followed a chronological or linear sequence. There are a few jumps, but overall we remain with Laure as she waits for her new dawn. It’s when she encounters Jean, however, that the film’s rhythm changes. In the traffic jam, Denis begins to utilize cross-fades which effectively emphasize a blurring of spaces and time. Laure’s face is overlaid with exterior shots of buildings, and Denis’ camera travels over the streets of Paris—which Laure can’t do physically—and trains on the faces in the other cars. Where we “are” and where Laure “is” quickly become intentionally confused. Even how long Laure has been stuck in traffic remains unclear.

The first look at Jean disrupts this roving as the camera fixes on his face, but his insertion into the narrative doesn’t trigger a simple trajectory. When he gets into Laure’s car, hoping to warm up from the cold night, she says, “I didn’t hear where you wanted to go.” “Leave me where you want,” he replies; he, too, has no clear path. Indeed, Jean’s presence quickly becomes an entirely careening force: the two strangers act on a feel-good, serendipitous spark and impulsively plan to get dinner, but in the moment when Laure steps out of her car to place a call to cancel her existing plans, Jean stages a flustering coup, hastily directing Laure to the passenger seat and taking the wheel. Immediately and fittingly, he speeds the car in reverse, taking Laure and the plot in a new, counterintuitive direction. The scene is intentionally disorienting, creating the sensation of being lost in both physical space and in time. And as Laure looks out the window and sees the street whip by backwards, she panics and demands to get out. Jean acquiescingly relinquishes control and leaves, and Laure reorients herself. Clearly exhilarated by the bizarre encounter, she follows the feeling and decides to seek him out, finding him at a small café, Le Rallye. It’s at this point, as Mayne says, that “gradually [Laure] settles into a state of pure sensation.”[vi]

Denis evokes this state of pure sensation by increasingly using extreme close-ups, and further toying with the film’s speed. When Jean asks for a 10 Franc piece to use the phone at La Rallye, Laure follows him downstairs; as they pass each other in the narrow staircase, the film slows for an instant as they’re forced to press up against each other while she descends and he returns to the café. This small moment takes on a new scale and time of its own, as it’s the first real cue they’ll sleep together. (Immediately after, Laure notices the payphone only accepts cards while the condom machine that’s right beside it—oh-so French—takes 10 Franc coins.) When the pair make their way to a hotel, a moment in the lobby is shot entirely differently from the sex scene that’s to come: Denis takes a medium frame as the clerk checks them in (and checks them out with barely disguised curiosity that’s mingled with judgment), but a sense of disembodiment is evoked once again as soon as they enter their vacant room, the camera training on their hands, necks and feet. It’s not a formulaic procession from kissing to disrobing to sex that Denis depicts so much as a collage of images of sensual touch that, when absorbed together, form a mosaic of desire. The only time this long scene of foreplay is “disrupted” is by a cutaway shot of a glowing red heater in their room, a playful visual nod to how hot Laure and Jean are getting.

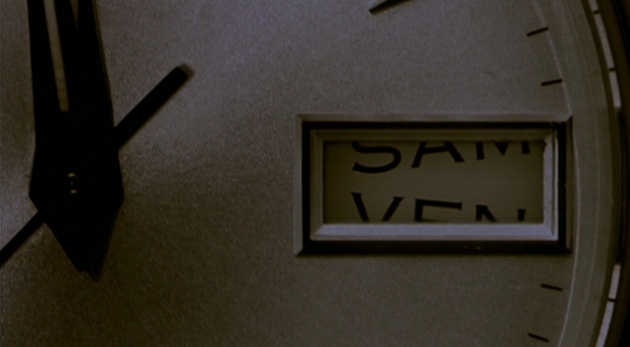

After sleeping together, Laure and Jean go out for pizza. Here, Denis overlays an image of Jean embracing Laure in bed over a shot of him at the table, evoking the continuity of desire as it seeps into this new environment. Unsurprisingly, then, the emphasis on touch—a form of communication that feels roving and ripe compared to the straightforwardness of dialogue—lingers in the café as the camera trains on Laure stroking Jean’s arm and working her fingers under his sleeve. Touch is recalled once again when they return to the hotel: as Laure hangs Jean’s coat, the film shifts momentarily to slow motion as she drags her hand down the sleeve. It’s the last moment of pure present; in the cafe there’s an insert shot of a watch face as the day rolls over from Friday to Saturday. Time very much rears its head, and for a brief moment a shot of Laure’s boxed-up apartment appears. In the hotel, a naked and presumably post-coital Laure puts on Jean’s coat and wanders the empty halls, relishing being alone for the moment in a new space. She’s quickly back in bed, however, embracing Jean again. As dawn breaks over Paris—Denis once again shoots the iconic rooftops, this time reemerging from darkness—Laure dresses and slips out of the hotel, leaving Jean sleeping. In the streets, she begins to walk, then run, though in no one direction. A sequence of shots shows her running in seemingly opposite directions, perhaps in search of her car, or perhaps in search of something far more intangible. In the final scene, she rounds a corner and the film slows again, capturing the spread of a smile across Laure’s face as she runs off towards the unknown.

Examining the aesthetic and narrative modes of Let the Sunshine In and Friday Night side by side offers a greater picture of Denis’ complexly beautiful approach to representing desire and positions the theme as one to be taken seriously in her work; in Denis’ filmmaking, we locate a cinematic space where the immediacy of women’s wants and needs is foregrounded, indulged and generously examined. The two films also offer alternative visions of where love can take us, subverting traditionally-attached notions of convention, linearity, and the culturally- or state-sanctioned ritual of marriage. In Let the Sunshine In, Binoche’s character ends up not consciously coupled, but right where she began: searching. In Friday Night, the aesthetic shapes the story, shifting our focus toward the intensity of the moment with close-up shots and fragmented editing. As a result, its ending feels endlessly liberating for Laure; instead of focusing on what’s to come or what once was mere moments ago with Jean, the emphasis remains on Laure in the present—in the beat after the past slips by and before the future arrives. It’s a rare moment of radical presence, nearly impossible to capture, and in Denis’ films entire worlds can be experienced in these precious instants. If we’re very lucky, like Laure, when we do experience them we leave with a smile on our face.