The filmmaker Peggy Ahwesh recalled the summer of 1983, which she spent in Pittsburgh, as “a very hot summer.”[i] Indeed, temperatures reached almost 100°F in a city known for seasonal climates both steamy and sticky. That year Ahwesh would develop her Pittsburgh Trilogy (Verite Opera, Paranormal Intelligence, and Nostalgia for Paradise), tying her filmic identity to the deindustrialized urban environment of her city and its arts scene, which was influenced by hometown heroes such as horror film director George Romero and artist Andy Warhol. Projects were pursued with friends and embodied the local do-it-yourself ethos. With her later film The Deadman (1989), on which she collaborated with Keith Sanborn, Ahwesh would take on one of Georges Bataille’s famously abject stories, the posthumously published “Le mort,” and, translated and adapted by her collaborator, situate it within her resident group of punks, experimenting with an erratic but explicitly feminist filmmaking lens.

I first saw Peggy Ahwesh and Keith Sanborn’s The Deadman at the Los Angeles gallery JOAN, screening alongside Kathy Acker and Alan Sondheim’s Blue Tape (1974). The two works were part of a program associated with the 2015 group exhibition Sylvia Bataille, which both centred and de-centred the mystifying biography of the titular Romanian-Jewish French film actress through the presentation of numerous contemporary artworks. She was married to the philosopher Georges Bataille, and later to the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan—two behemoths of contemporary Western critical theory. The exhibition provided a liminal space in which the curators attempted to recover the narrative of a woman who did not figure explicitly into the canonical work of either Bataille or Lacan. Ahwesh’s project considered the overlapping ideas of the two thinkers, and still today exemplifies how filmmaking and contemporaneous psychoanalytic thinking began to incorporate the political concerns of feminism.

The primary works that would inform the practice of Ahwesh and her contemporaries began to emerge in the 1970s: Juliet Mitchell’s Psychoanalysis and Feminism was printed in 1974, and Laura Mulvey’s groundbreaking feminist film analysis, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” which employed Freudian and Lacanian critical methodologies, was published in Screen the following year. Developments in psychoanalytic feminism not only suffused film criticism, but also migrated into the practices of women artists, such as dancer Yvonne Rainer and photographer Cindy Sherman, who were considering the complex relationship between looking and desire, as well as its gendered expectations. As the discourse and vocabulary of psychoanalytic feminism began to circulate, scholars noted the untranslatable nature of the Lacanian understanding of jouissance. The term “enjoyment” failed to capture the affect’s innately sexual connotation. In the pursuit of pleasure, jouissance tests and explores the boundaries of one’s desire.

Ahwesh once described The Deadman as “one long female jouissance.”[ii] Shot on 16mm, The Deadman features Jennifer Montgomery as the main character Marie, a woman in reckless pursuit of orgiastic bliss over the film’s 37-minute run time. In the film, Ahwesh allows the female protagonist to investigate her own limits, relishing in her own fantasy and interrupting the scopophilic tendencies of the apparatus that lock in a determined gaze.

The film begins with a depiction of the titular character’s last living moments. The viewer hears someone breathing with difficulty, or perhaps lustfully panting, and an eventual crash. A fly buzzes in the background. The camera zooms in on a swaying light fixture. A naked man is sprawled out on a bed on top of many pillows. Marie runs out of the house wearing only shoes and a thin trench coat. She barrels into the woods, where she squats and urinates—a form of gratifying release— and then continues on, racing through the rain.

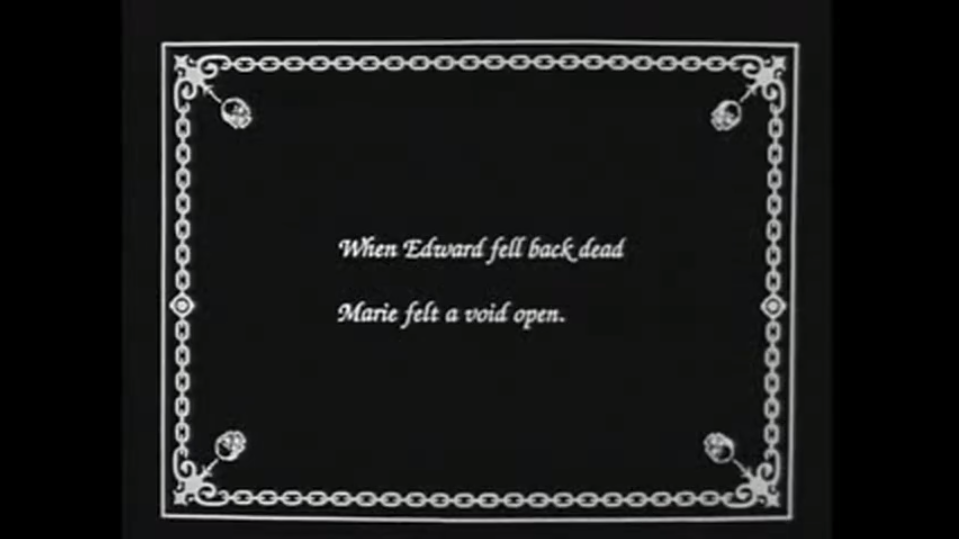

The opening scene in which Marie’s male lover perishes proves catalytic: the intertitle literally reads, “When Edward fell back dead, Marie felt a void open.” The philosopher Julia Kristeva explicitly tied the unmooring vertigo of jouissance to its ability to afford a woman a space outside of the drudge of linear time, cleaving a moment where female subjectivity can be realized.[iii] Time is, if not forgotten, then reconfigured in The Deadman, and becomes a tool Ahwesh utilizes to a significant degree.

Time is, if not forgotten, then reconfigured in The Deadman, and becomes a tool Ahwesh utilizes to a significant degree.

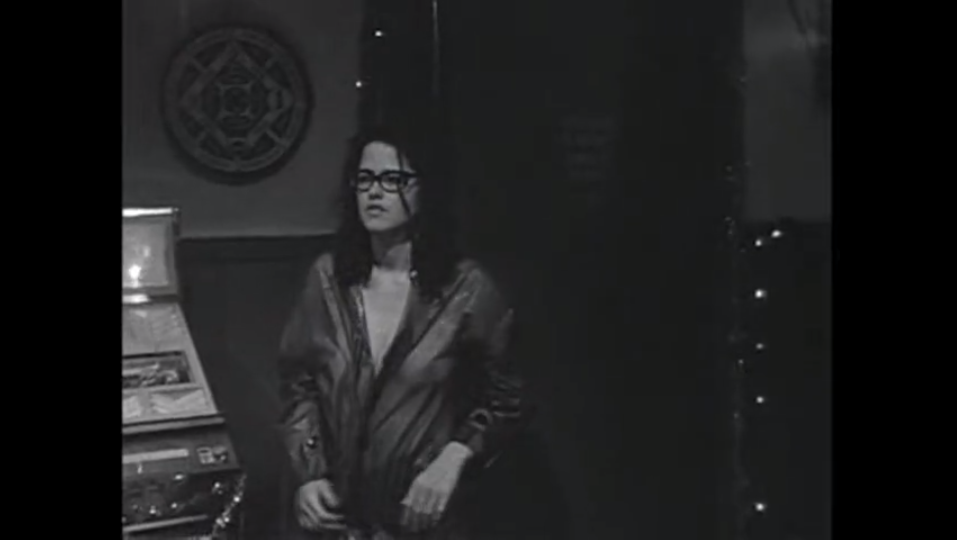

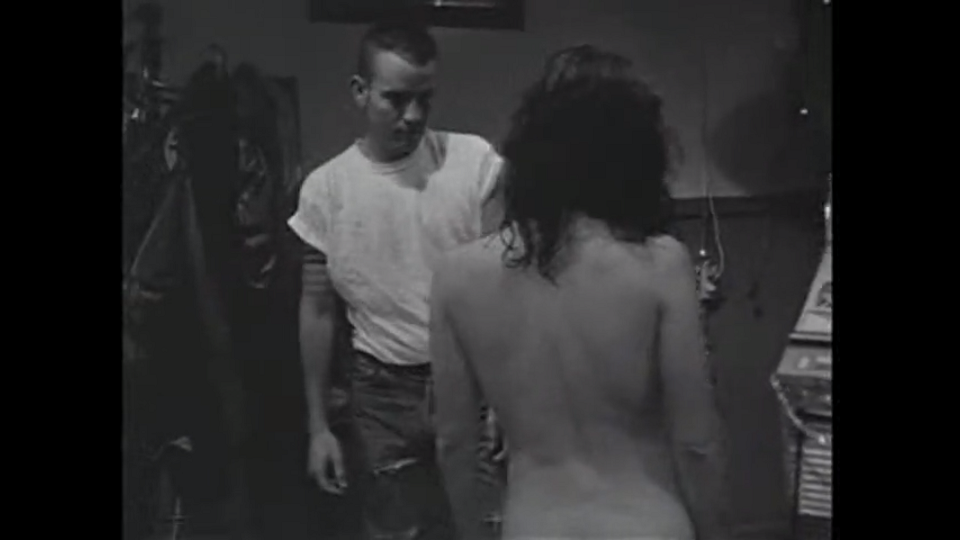

On her meandering journey, Marie encounters a bar, enters, and makes herself known to the patrons and the barkeep. There’s no better word for what transpires than confrontation: she begins chugging whiskey with two “farmboys” and centres the attention of everyone else in the room on her being. She loudly burps after pounding a glass, and then hangs up her already revealing wet coat, unveiling her naked body, taut and elastic. A drunk and disorderly man wearing a shirt emblazoned with the words “COSMIC DEBRIS” is brusquely unzipped and exposed by Marie; everyone cheers. Another intertitle flashes: “The dick raised a great burst of laughter.”

Sanborn’s adapted script of Bataille’s text is both narrated in voiceover and communicated through intertitles, lending an antiquated silent film-era quality to the movie. Conversely, the film’s score traverses different temporalities. The Kinks’ “Sunny Afternoon” hums in the background as Marie enters the bar; a tango overlaid with a velvety midcentury crooner closes the film, echoing a scene in the film’s middle in which Marie sloppily and awkwardly dances with Pierrot, a handsome ruffian by the jukebox who has taken her interest.

Marie and Pierrot’s meeting unleashes an altogether-new level of transgression in Ahwesh’s filmic world. The two begin to wrestle and fight. Non-diegetic laughter is sprinkled throughout these scenes. In addition to the grinding and writhing of bodies, the acting in the film is gloriously irreverent: Ahwesh’s troupe revels in the bawdy humor of its players. Montgomery hams it up for the camera in the role of Marie, her limbs swinging strong and sure.

“Fuck me!” she begins to repeat robotically with a harsh edge in her voice; she soon achieves another “death spasm” after hate-fucking Pierrot on the floor of the bar. The encounter is assisted by the Count, a new arrival who appears amid the melee and enrobes Pierrot’s dick with a contraceptive while Marie waits impatiently— a nod to the sexual precautions pushed post-peak AIDS crisis. The Count’s paternalistic meddling is indicative of the disruptive, antagonistic force he seems to represent to Marie, who is convinced he’s the ghost of her dead lover.

Through the intertitles and narration, the release of death is increasingly portended.

When Marie comes, the camera cuts to a shot of her waking up in nature, birds chirping in the background and trees swaying in the wind. The Count approaches her figure in the idyll a moment later, and she stands, vomiting at his feet before then defecating in her own vomit. When the Count idly propositions her, Marie becomes agitated and combative, signaling the disorder to come. Through the intertitles and narration, the release of death is increasingly portended.

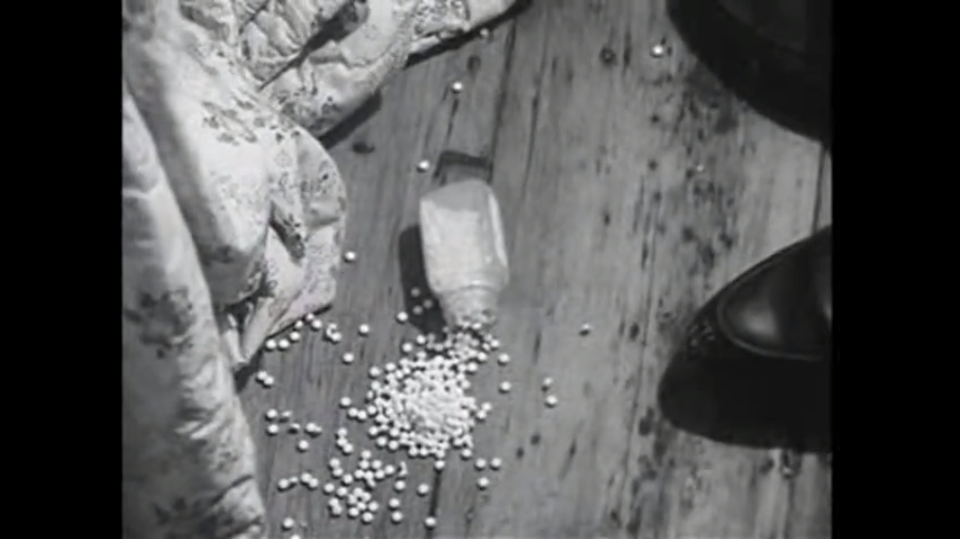

Marie and the Count return to the house featured in the opening, and Marie sits next to the now-rotting corpse of the “deadman”. She collapses suddenly in view of the now-shaken Count, and a bottle of pills overturns onto the floor. The camera then cuts to a view of the Count elsewhere, violently heaving into a dumpster on a busy street. We follow him to a funeral procession that has made its way into a cemetery, where a fire burns brilliantly. And then, The Count stumbles haphazardly into a muddy expanse. Another “deadman”; another release.

In The Deadman, Marie strongly personifies the abject, which Kristeva closely ties to jouissance, and journeys into a territory of female desire that both traditional modes of film and pornography fail to capture.

The Deadman forms part of the loosely assembled love/sex trilogy that includes The Color of Love (1994) and Nocturne (1998). Ahwesh has emphasized the non-narrativity of these films and insists on their exploration of numerous affective textures. In The Deadman, Marie strongly personifies the abject, which Kristeva closely ties to jouissance, and journeys into a territory of female desire that both traditional modes of film and pornography fail to capture. Art historian Hal Foster helpfully summarizes Kristeva’s definition of the abject as “what I must get rid of in order to be an I at all…[and] abjection is a condition in which subjecthood is troubled, ‘where meaning collapses.’”[iv] The porous boundaries and limits of the desiring self are represented in the corpses and ghosts that litter The Deadman, which borrows visual tropes from early vampire films and late 1960s zombie-horror movies. (Early in her career Ahwesh took a job at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, an art venue where she screened a film series that included Romero’s Night of the Living Dead; she later joined the crew of his 1982 film Creepshow as a production assistant. [v]) Produced 15 years after The Deadman, Nocturne similarly opens with a scene of a naked man, seemingly dead. In it, the camera cuts to a frantic spider—a being often symbolic of femininity—spinning a web, and an educational voiceover gravely muses: “Beneath the beauty of nature’s world is one single and ugly truth: life must take life, in the interest of life itself…If any living species is to inherit the earth, it will not be man.”

Ahwesh was mindful of the psychoanalytic frameworks being investigated by other feminist filmmakers at the time, consciously and deliberately choosing to engage with these women artists and directors. From 1972 to 1978 she studied at Antioch College with, among others, structural filmmakers Paul Sharits and Tony Conrad [vi], but recalls the particular pedagogical influence of the artist Janis Lipzin, who had organized an exhibition inviting Carolee Schneemann, Beverly Conrad and Joyce Wieland to present their work. Ahwesh has called The Deadman a response to Yvonne Rainer’s film The Man Who Envied Women (1985), which she described as “a really knowledgeable, thought-through Lacanian position…the woman can’t even be in the movie because she’s so misunderstood and misrepresented by language and imagery.” [vii]

The porous boundaries and limits of the desiring self are represented in the corpses and ghosts that litter The Deadman, which borrows visual tropes from early vampire films and late 1960s zombie-horror movies.

The Deadman’s star Montgomery, a filmmaker herself, met Ahwesh at the San Francisco Art Institute in the 1980s,[viii] where they started collaborating. They moved to New York together, and Montgomery studied with Rainer at the Whitney Independent Study Program, making films about her own life on Super-8 and participating in the city’s burgeoning experimental filmmaking circle. The cut-and-paste pastiche, rudimentary acting, and diablerie were customary to Ahwesh’s punk and No Wave milieu, which gripped downtown New York in the 80s.

Filmmaker Bradley Eros, who is cited in Nick Zedd’s 1985 “Cinema of Transgression Manifesto,” is credited multiple times in Ahwesh’s work. In the manifesto, which made its appearance in a zine called the Underground Film Bulletin, Zedd wrote:

Since there is no afterlife, the only hell is the hell of praying, obeying laws, and debasing yourself before authority figures, the only heaven is the heaven of sin, being rebellious, having fun, fucking, learning new things and breaking as many rules as you can. This act of courage is known as transgression.[ix]

Ahwesh’s oeuvre was not directly associated with the Cinema of Transgression movement, but her approach to filmmaking makes similar leaps of faith and the narratives and imagery utilized in The Deadman work within the same modalities. The director’s work shares affinity with artists from the movement like Tessa Hughes-Freeland and Kembra Pfahler who used bricolage to assemble fictions that bore witness to the formation of female subjectivity and spun fantasy that appealed to women. The work of Transgression filmmaker Richard Kern also bears similarity of spirit: his sexually explicit, proto-Suicide Girls output paired alt-personalities such as Lung Leg and Lydia Lunch with newts and daggers as the women danced seductively albeit awkwardly for the camera. The female protagonists were steely but the camera was still voyeuristic, as in work like his 1986 short film Submit to Me.

In The Deadman, the destructive forces inherent in abjection yield new generative space which, together with Ahwesh’s subversive treatment of time, seem to summon the ushering-in of a new paradigm altogether. The void Marie encounters holds space enough for new explorations of her pleasure and assertiveness in proportions so considerable they appear almost intoxicating; presented is a poignant mobilization of traditional images and notions of femininity disrupted by the grotesque and an ethos of reckless abandon. Blending the influence of psychoanalytic feminist thought, the brazenness of horror film imagery and experimental sensibilities, Ahwesh and Sanborn bring attention to a new possible subjectivity: The Deadman fashions a cocoon from the void.