If I’m no good at pretending to be a man and no good at being young, I might just as well start pretending that I am an old woman. I am not sure that anybody has invented old women yet; but it might be worth trying.

— Ursula K. Le Guin, “Introducing Myself,” The Wave in the Mind

What does it mean for a woman to be herself, play herself, tell her own story? Since her first film, La Pointe Courte (1954), Agnès Varda’s work has been read in relation to her anomalous status as the “only” woman of the Left Bank or Nouvelle Vague (erasing significant figures such as Marguerite Duras and Anna Karina), and simultaneously as forever “introducing herself” through and into her work. In recent public appearances, she has drawn attention to this persistent singularity. On receipt of a lifetime achievement award at the European Film Awards in 2014, she observed of the room:

I feel there are not enough women. I think more women should be included. I know a lot of very good female directors and women editors and I would like them [to] be more represented and helped by the European film academy.[i]

As Agnès Varda’s contemporary Ursula K. Le Guin notes in her performance piece “Introducing Myself,” however, “Women are a very recent invention. I predate the invention of women by decades.” Like Le Guin, Varda started to make work at a time when she had to introduce herself as a woman artist – and she has persisted in doing so. In The Gleaners and I (2000), the filmmaker describes herself as “filming one hand with the other hand.” In doing so, she too “invented old women” – studying her wrinkles, reflecting her face in a Lucite clock without hands. Yet she told journalist Gaby Wood in 2015, “when I was 30 years old they called me ‘grandmother’ [of the Nouvelle Vague]. I started to get old at a very young age.”[ii]

In her subsequent documentary The Beaches of Agnès (2008), she appears as a grandmother with her grandchildren, looking back over her years as a so-called ‘grandmother’. She refracts her life story into dozens of mirrors like those set up on the beaches of her childhood in the film’s opening. Setting up echoes between Varda’s lived experiences and their translation into cinema, Beaches of Agnès poses an omnivalent question: can a woman artist ever – even in her 80s, after making work for 50 years – do more than introduce herself? Varda, of course, has the answer.

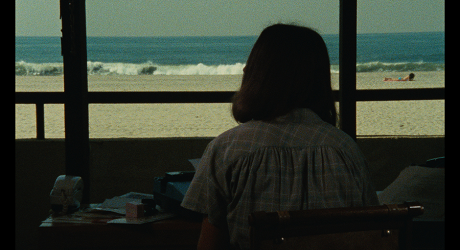

In her mid-length fiction feature Documenteur (1981), Emilie, a divorced mother, lives with her young son Martin in Venice Beach. She works as a secretary for a film company and looks out at the sea. The film’s title puns on the French word for documentary, documentaire, and the word for liar, menteur. It suggests that no authentic documentation is possible – but also that the film is not fiction. As Michael Koresky notes in the film’s Criterion Eclipse DVD notes, Emilie is played by Sabine Mamou, who was concurrently editing Varda’s Los Angeles documentary Mur Murs (1980), a tone-poem that traces murals as markers of the city’s multiple ethnic and socio-economic communities and the borders where they meet. Varda herself was living in Venice Beach at the time with her son Mathieu, separated from her husband Jacques Demy.

Documenteur was far from the first film that Varda made containing autobiographical resonances. La Pointe Courte was filmed in the small town where she spent WWII as a child, and her documentaries L’opéra mouffe (1962) and Daguerréotypes (1976) both explored the intimacies of her Paris neighbourhood. In Lions Love (… and Lies) (1969), made during Varda’s first trip to LA with Demy, documentary filmmaker Shirley Clarke plays a documentary maker on screen in a gesture of self-reference, while also standing in for Varda, the director behind the camera.

Or does she? Clarke both does and does not stand in for Varda; for she, too, was a filmmaker who moved between heightened, performative documentary and observational, improvisational drama. In the film, Clarke plays a documentary maker; Varda presents Lions Love as fiction. Clarke is American; Varda, French. Yet the whole project is concerned with the tensions between displacement and authenticity – between those 1960s ideals of dropping out and keeping it real – as California hippiedom is embodied by three counter-cultural New Yorkers (James Rado and Jerome Ragni, who created Hair, and Viva Hoffmann). Clarke’s explosive entrée into the threesome’s life is clearly a reference to her invasive interview technique in her Portrait of Jason (1967).

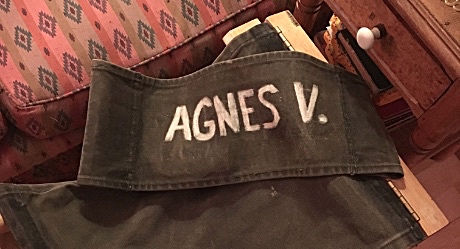

Perhaps one of Varda’s answers, then, is that she is not alone: there are other women inventing and introducing themselves as well, observing and refracting each other. Her films with Jane Birkin (Jane B. par Agnès V. and Kung Fu Master!, both 1988) offer a similar sense of resonance as the friends dissect the complexity of celebrity, feminism, motherhood and female desire. That Varda cast her son Mathieu as the teenage boy with whom Birkin falls in love (Birkin’s daughters are played by her real-life daughters Charlotte Gainsbourg and Lou Doillon) adds a provocative pulse to the film.

Perhaps one of Varda’s answers, then, is that she is not alone: there are other women inventing and introducing themselves as well, observing and refracting each other.

Mathieu also appears in Documenteur, as Emilie’s young son. But does Varda? Recasting herself as Emilie, a secretary – transcribing the script for Mur Murs – Varda actively questions, and even excoriates, the politique des auteurs coined by François Truffaut in Cahiers du cinéma. In her catalogue raisonée Varda par Agnès, Varda performs an incredible manoeuvre on the word cahiers (notebook), beginning by reminiscing about her mother’s journals:

Dare I launch into a leap from my mother’s notebooks to Cahiers du cinéma? This famous journal, which I didn’t know at all, until I met some of the team for the first time one evening in the winter of ‘54-‘55, when they demanded to see [Alain] Resnais, who invited them in. This was during the edit for La Pointe Courte.[iii]

She re-inserts the heavily masculine élite film journal into the domestic and maternal; in Documenteur, she makes a similar move with the auteur, in a critique of the idea of independence. For Emilie, independence is loneliness.

Yet, even in this spare film, there are also echoes of what Corinn Columpar calls the auteure, in an essay on Sally Potter’s self-starring film The Tango Lesson (1996)[iv]. The auteure, marked by a feminist difference, combines a quizzical reflexivity about her authorship with a foregrounding of the collaborative nature of creative practice, at once signing herself as creator and recognising her work as necessarily collective. Emilie, the secretary, becomes the de facto author of Mur Murs, as she is asked to deliver the voice-over as well as transcribing the playful, punning script that is Varda’s hallmark.

Documenteur is in some ways the least self-reflexive and most plangent of Varda’s fiction films, without the jeu d’ésprit of the musical numbers of her previous feature L’Une chante, l’autre pas (One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, 1976) – and also apparently without the female kinship that underlies that film. Yet there is a partnership and doubling here as resonant as Varda/Clarke, and a sign of auteure-ial collaboration: whereas Varda narrates L’Une chante, the narrator of Documenteur is Delphine Seyrig, Varda’s close friend and feminist co-conspirator. In Beaches of Agnès Varda talks gleefully about Seyrig’s transformation from the très fey Fée de Lilas in Peau d’âne (Donkeyskin, 1969), directed by Demy, into a hardcore feminist activist. By 1981, Seyrig was internationally known for her work with two other Francophone women filmmakers: Chantal Akerman, for whom she played Jeanne Dielman, and Marguerite Duras; as well as radical video artist Carole Roussopoulos, with whom her projects included a reading of the SCUM Manifesto[v].

Thus, Seyrig’s voice on the soundtrack connects Varda (back) to a feminist film community in France. The lingering shots from the window echo similar shots in Duras’ two Aurelia Steiner films (1979 and 1980), while the quietist focus on a maternal figure in domestic space could be read as a tribute to Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1976). As I’ve written elsewhere[vi], film critics traditionally pay too little attention to women filmmakers’ homocitation – we miss the communities they build, introducing themselves as multiple, communal, complex and – above all – attentively discursive.

When Varda recently visited the Criterion closet[vii], she made a grab for two of the few female filmmakers whose films are distributed by the DVD label: Jane Campion and Lena Dunham. She comments: “An Angel at My Table [1990] and Sweetie [1989], the two of Jane Campion, the early films she made that I love so much; so sensible, so intelligent.” Varda offers a key descriptor for her own films here. In French, sensible is closer to the sensibility of Jane Austen’s Sense and…, an awareness of and immersion in feeling that resonates with Documenteur’s subtitle: An Emotion Picture.

Not only is Varda establishing a genealogy in choosing Campion’s and Dunham’s films, she also engages obliquely with current debates around the autobiographical and confessional within feminism, for which Dunham is a lightning rod. Emotion is often positioned as a marker of authenticity of experience – but also, by misogynist critics, as a lack of creative transformation or craft. Unlike Campion (who novelised her films The Piano and Holy Smoke, filmed adaptations of An Angel at My Table, Portrait of a Lady and In the Cut, and made Bright Star about the poet John Keats), Varda is not an overtly literary filmmaker – and yet her cinematic approach bears close resemblance to the genre that dominates late 20th century French women’s writing: autofiction. Although not initially defined as feminist, this genre-blurring practice offers strategic value to women artists introducing themselves: formally, it often uses mirroring and doubling, self-reflexive performance and generic/stylistic hybridity, echoing the splitting of female experience under patriarchy; yet these formal strategies also allow for the recognition of a plural or multiple subjectivity that confounds the notion of direct autobiographical representation.

Varda has sustained her variety, not just as play (like the mirrors on the beach), but to explore formerly unrepresented or taboo subjects. In Visages villages (Faces Places, 2017), she offers yet another variation of herself: Varda the partially-sighted filmmaker, collaborating with the mysterious, sunglass-wearing JR – his always-attached eyewear mirroring that of her former collaborator and friend Godard (who appears in his sunglasses in the film-within-a-film in Cléo de 5 à 7 [1962]). As JR creates wall-sized poster prints of portraits, Faces Places circles back on Mur Murs and the power of walls to hold up the image of communities – but with a new viewer in mind, that of a person with macular degeneration for whom scale makes all the difference. And so Varda introduces herself yet again, as we see her getting shots from her ophthalmologist.

The film ends with a blurred shot of a glasses-less JR. It may seem like a loss to some – of correct focus and film form, of the political emphasis on the solitary director as creative genius – but that fuzzy shot sums up what Varda has added to cinema: an insistence on her unique vision, shared with unique generosity, through reciprocal looking. Losing her sight, she finds a new way to see with and through the camera; a new way to show us how she experiences seeing. It’s poignant, witty, totally cinematic – and sensible, a meeting of sensitivity and practicality utterly Varda-esque.

It’s telling that – unlike Godard/ian – Varda does not have an adjective.

Vardadian? It’s telling that – unlike Godard/ian – Varda does not have an adjective. Yet her championing of Campion, and of female filmmakers tout court, suggests that we need one. As Faces Places wins La Varda her first “real” Academy Award nomination (she famously referred to her honorary 2017 Oscar as “the side Oscar” and “the Oscar of the poor”[viii]), it’s time to coin an adjective to salute her filmmaking, whose variety is always rooted in – and created by – her own, so that we can talk (in years to come) of many and various female filmmakers’ Vardadiation.